Sexual spores in fungi, known as meiospores, are produced through a complex reproductive process that involves the fusion of compatible haploid hyphae or gametes, followed by meiosis. This process typically occurs within specialized structures such as fruiting bodies or sporangia. In most fungi, sexual reproduction begins with the formation of gametangia, which house the gametes. When two compatible individuals come into contact, their gametes fuse, resulting in a diploid zygote. This zygote then undergoes meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores. These spores are often encased in protective structures, such as asci in Ascomycetes or basidia in Basidiomycetes, before being dispersed into the environment to germinate and form new fungal individuals. This mechanism ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in fungal populations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Name | Sexual reproduction in fungi involves the formation of meiosis-derived spores. |

| Types of Spores | Ascospores (in Ascomycetes), Basidiospores (in Basidiomycetes), Zygospores (in Zygomycetes), Oospores (in Oomycetes). |

| Key Structures | Ascus (sac-like structure in Ascomycetes), Basidium (club-shaped structure in Basidiomycetes), Zygosporangium (thick-walled structure in Zygomycetes). |

| Plasmogamy | Fusion of hyphal cells (somatogamy) or gametangia (gametangial contact), leading to the merging of cytoplasm. |

| Karyogamy | Fusion of haploid nuclei from compatible hyphae or gametangia, forming a diploid zygote. |

| Meiosis | Occurs within the zygote or sporogenous cells, reducing the chromosome number to haploid. |

| Sporogenesis | Haploid nuclei divide mitotically to produce multiple sexual spores within the ascus, basidium, or sporangium. |

| Dispersal | Spores are released through rupture of the ascus/basidium or active discharge mechanisms (e.g., ballistospore discharge). |

| Environmental Triggers | Often induced by nutrient depletion, stress, or hormonal signals (e.g., alpha and a-factor pheromones in yeasts). |

| Genetic Diversity | Promotes genetic recombination through crossing over during meiosis and random assortment of chromosomes. |

| Ecological Role | Ensures survival in adverse conditions, facilitates colonization of new habitats, and enhances adaptability. |

| Examples | Penicillium (Ascomycetes), Agaricus (Basidiomycetes), Rhizopus (Zygomycetes). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangiospore Formation: Sporangiospores develop inside sporangia, structures produced by certain fungi via asexual reproduction

- Zygospores Creation: Zygospores form when haploid hyphae fuse, creating a thick-walled zygote in fungi

- Ascospore Development: Ascospores mature inside sac-like asci, produced during sexual reproduction in Ascomycetes

- Basidiospore Production: Basidiospores grow on basidia, club-shaped structures in Basidiomycetes, released for dispersal

- Oospore Generation: Oospores result from fertilization of oogonia by antheridia in Oomycetes, ensuring survival

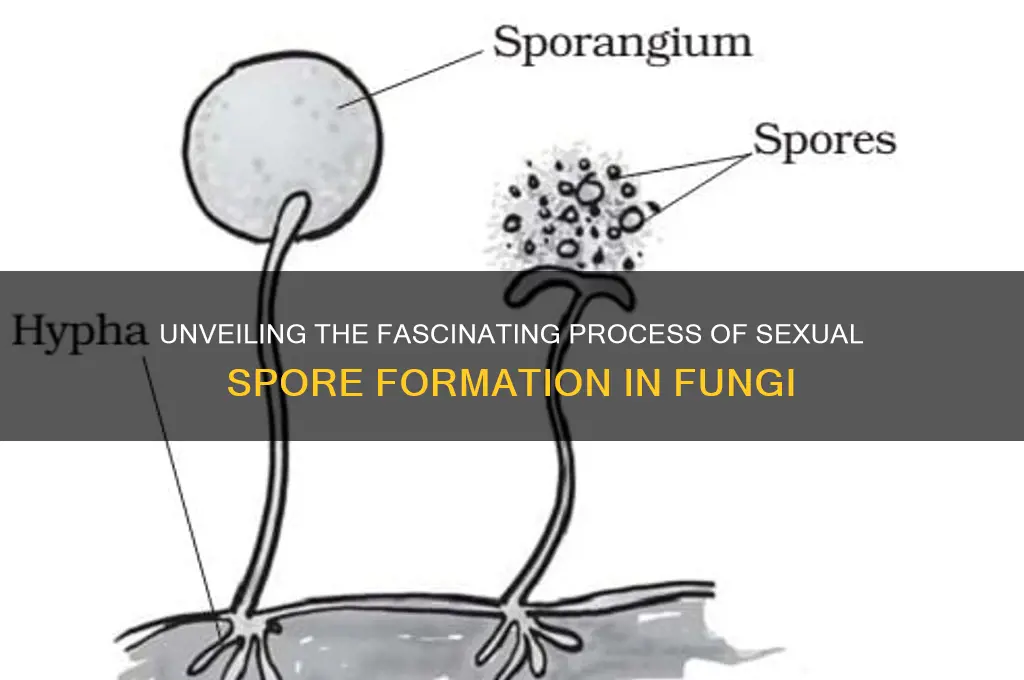

Sporangiospore Formation: Sporangiospores develop inside sporangia, structures produced by certain fungi via asexual reproduction

Fungi employ diverse strategies for reproduction, and sporangiospore formation stands out as a fascinating asexual method. Unlike sexual spores, which result from the fusion of gametes, sporangiospores develop within specialized structures called sporangia, showcasing the ingenuity of fungal life cycles. This process, prevalent in zygomycetes and certain other fungi, offers a rapid and efficient means of propagation under favorable conditions.

Imagine a microscopic balloon inflating with countless spores. That's akin to a sporangium, a sac-like structure formed at the tip of a specialized hyphal branch called a sporangiophore. Within this protective chamber, haploid sporangiospores are produced through mitosis, ensuring genetic uniformity. This asexual nature allows for swift colonization of new environments, a crucial advantage in the competitive world of microorganisms.

As the sporangium matures, it undergoes a transformation. The sporangium wall dries and ruptures, releasing the sporangiospores into the environment. These lightweight spores, often equipped with structures aiding dispersal like elaters (coiled appendages), are carried by air currents or other means to new locations. Upon landing in a suitable habitat, they germinate, giving rise to new fungal individuals genetically identical to the parent.

While efficient, sporangiospore formation has limitations. The lack of genetic diversity inherent in asexual reproduction can hinder adaptation to changing environments. Furthermore, the reliance on favorable conditions for spore release and germination makes this strategy vulnerable to environmental fluctuations. Understanding these intricacies highlights the delicate balance between rapid propagation and long-term survival strategies employed by fungi.

Are Spores Alive? Unveiling the Mystery of Their Release and Viability

You may want to see also

Zygospores Creation: Zygospores form when haploid hyphae fuse, creating a thick-walled zygote in fungi

In the intricate world of fungal reproduction, zygospores stand out as a remarkable example of sexual spore formation. Unlike asexual spores, which are produced through mitosis, zygospores are the product of a sexual union between two haploid hyphae. This process, known as zygospore creation, is a critical survival mechanism for certain fungi, particularly in the Zygomycota phylum. When environmental conditions become unfavorable, such as during drought or nutrient scarcity, compatible haploid hyphae from different mating types fuse, initiating a cascade of events that culminates in the formation of a thick-walled zygote. This zygote, or zygospore, is a resilient structure capable of withstanding harsh conditions until more favorable circumstances allow for germination and growth.

The fusion of haploid hyphae is a highly regulated process, involving the recognition of compatible mating types through pheromone signaling. Once compatibility is confirmed, the cell walls between the hyphae dissolve, allowing the cytoplasm and nuclei to merge. This fusion results in a diploid zygote, which then undergoes karyogamy, the union of the two haploid nuclei. The zygospore wall thickens, providing protection against desiccation, predation, and other environmental stresses. This thick wall is composed of complex polysaccharides and chitin, making it a formidable barrier. The entire process is a testament to the adaptability and resilience of fungi, ensuring their survival across diverse and often challenging ecosystems.

From a practical standpoint, understanding zygospore creation has significant implications for agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. For instance, zygospores of certain fungi, such as *Rhizopus* and *Mucor*, are known to cause food spoilage and infections in immunocompromised individuals. By disrupting the mating processes or targeting the zygospore wall formation, researchers can develop strategies to control these fungi. In biotechnology, the resilience of zygospores inspires the design of durable storage methods for biological materials. For hobbyists and educators, observing zygospore formation under a microscope can be a fascinating way to explore fungal biology. To do this, one can culture compatible strains of Zygomycota on a nutrient-rich medium, such as potato dextrose agar, and monitor the colonies for signs of zygospore development over several days.

Comparatively, zygospore creation contrasts with other sexual spore formation methods in fungi, such as the production of asci in Ascomycetes or basidia in Basidiomycetes. While these structures also result from sexual fusion, zygospores are unique in their simplicity and robustness. Unlike the multicellular structures of asci and basidia, zygospores are single-celled and highly specialized for survival. This distinction highlights the diversity of reproductive strategies in the fungal kingdom, each tailored to specific ecological niches. For example, the rapid dispersal of ascospores and basidiospores is ideal for colonizing new habitats, whereas zygospores excel in enduring adverse conditions.

In conclusion, zygospore creation is a fascinating and essential process in the life cycle of certain fungi. By fusing haploid hyphae to form a thick-walled zygote, these organisms ensure their survival in challenging environments. This mechanism not only showcases the ingenuity of fungal biology but also offers practical insights for various fields. Whether you're a researcher, educator, or enthusiast, exploring zygospore formation provides a deeper appreciation for the complexity and adaptability of the fungal world. With simple laboratory techniques, anyone can witness this remarkable process firsthand, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and hands-on discovery.

Yeast Spore Germination: Unveiling the Intricate Process of Awakening

You may want to see also

Ascospore Development: Ascospores mature inside sac-like asci, produced during sexual reproduction in Ascomycetes

Fungi, nature's master recyclers, employ diverse strategies for sexual reproduction, and the Ascomycetes, or sac fungi, have perfected a unique method: ascospore development. This process hinges on the formation of a specialized structure called the ascus, a microscopic sac that cradles and nurtures the developing ascospores.

Imagine a tiny, elongated balloon, often club-shaped, within which eight haploid spores are meticulously crafted. This is the ascus, the birthplace of ascospores.

The Journey Begins: From Hyphal Fusion to Ascogonium

Ascospore development commences with the fusion of two compatible hyphae, the filamentous structures that make up the fungal body. This union, known as plasmogamy, results in a dikaryotic cell, containing two distinct nuclei. From this point, a specialized structure called the ascogonium develops. Think of the ascogonium as the womb of the ascus, where the magic of meiosis and subsequent mitosis unfolds.

As the ascogonium matures, it elongates and differentiates into the ascus, a process triggered by environmental cues like nutrient availability and humidity.

Meiosis and the Birth of Ascospores

Within the ascus, the dikaryotic nucleus undergoes meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in four haploid nuclei. These nuclei then divide mitotically, producing eight haploid nuclei, each destined to become an ascospore.

Maturation and Release: Preparing for Dispersal

As the ascospores mature, they accumulate storage compounds like lipids and carbohydrates, essential for survival during dispersal and germination. The ascus wall thickens, providing protection during this vulnerable stage.

Ultimately, the mature asci rupture, releasing the ascospores into the environment. This release can be passive, relying on wind or water currents, or active, involving mechanisms like forcible ejection.

Significance and Applications

Understanding ascospore development is crucial for various fields. In agriculture, ascospores of beneficial fungi can be used as biofertilizers or biocontrol agents. Conversely, pathogenic Ascomycetes, like those causing powdery mildew or apple scab, rely on ascospores for disease spread, making knowledge of their development vital for disease management. Furthermore, the study of ascospore formation provides insights into fungal evolution and the diversity of life on Earth.

Pasteurization and Botulism: Does Heat Treatment Eliminate Deadly Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Basidiospore Production: Basidiospores grow on basidia, club-shaped structures in Basidiomycetes, released for dispersal

In the intricate world of fungal reproduction, basidiospore production stands out as a fascinating process unique to Basidiomycetes, the group encompassing mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts. These sexual spores are not merely products of chance but are meticulously crafted on specialized structures called basidia, which resemble tiny clubs under a microscope. This process is a testament to the evolutionary sophistication of fungi, ensuring their survival and dispersal across diverse environments.

The journey of basidiospore production begins with the fusion of haploid cells, a pivotal step in the sexual cycle of Basidiomycetes. This fusion results in the formation of a diploid zygote, which then undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei. These nuclei migrate into the basidium, a structure that develops from the hyphae of the fungus. The basidium’s club-like shape is not arbitrary; it provides an optimal platform for spore development and release. Each of the four nuclei grows into a basidiospore, attached to the basidium by a slender projection called a sterigma. This attachment is crucial, as it ensures the spores are poised for efficient dispersal once mature.

Dispersal is the ultimate goal of basidiospore production, and nature has perfected this mechanism through millions of years of evolution. When the basidiospores are fully developed, they are released into the environment, often with the aid of environmental factors such as wind, water, or even animals. For instance, in mushrooms, the gills or pores underneath the cap are densely packed with basidia, maximizing the number of spores released. This strategic placement ensures that even a gentle breeze can carry thousands of spores to new habitats, increasing the fungus’s chances of colonization.

Practical observations of basidiospore production can be made by examining mature mushrooms. A simple yet effective method is to place a mushroom cap, gill-side down, on a piece of paper overnight. By morning, a spore print will have formed, revealing the color and pattern of the spores. This technique not only aids in species identification but also highlights the sheer volume of spores produced, underscoring the efficiency of this reproductive strategy. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, understanding this process provides deeper insights into fungal ecology and the role of Basidiomycetes in ecosystems.

In conclusion, basidiospore production is a marvel of fungal biology, combining precision, efficiency, and adaptability. From the fusion of haploid cells to the strategic release of spores, every step is finely tuned to ensure the survival and proliferation of Basidiomycetes. By studying this process, we gain not only a greater appreciation for the complexity of fungi but also practical knowledge that can be applied in fields ranging from mycology to conservation biology. Whether you’re a scientist, a forager, or simply a nature enthusiast, the world of basidiospores offers endless opportunities for discovery and wonder.

Gymnosperms: Do They Produce Spores, Seeds, or Both?

You may want to see also

Oospore Generation: Oospores result from fertilization of oogonia by antheridia in Oomycetes, ensuring survival

In the intricate world of Oomycetes, oospore generation stands as a testament to nature's ingenuity in ensuring survival. Unlike true fungi, Oomycetes—often referred to as water molds—employ a unique sexual reproduction process centered around oogonia and antheridia. This mechanism culminates in the formation of oospores, thick-walled structures designed to withstand harsh environmental conditions. Understanding this process not only sheds light on their resilience but also highlights their ecological significance, particularly in aquatic and soil ecosystems.

The journey begins with the fertilization of oogonia by antheridia, a process that mirrors sexual reproduction in higher organisms. Oogonia, the female reproductive structures, are typically larger and contain egg cells, while antheridia produce motile male gametes called antherozoids. These antherozoids swim through water films to reach the oogonia, a critical step that underscores the importance of moisture in Oomycete reproduction. Once fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote develops into an oospore, encased in a robust wall that provides protection against desiccation, temperature extremes, and predators.

From a practical standpoint, understanding oospore generation is crucial for managing Oomycete-related diseases in agriculture. For instance, *Phytophthora infestans*, the notorious cause of late blight in potatoes, relies on oospores to survive winter months in soil. Farmers can disrupt this cycle by reducing soil moisture through proper drainage or by applying fungicides at specific stages of the Oomycete life cycle. For home gardeners, rotating crops and removing infected plant debris can limit oospore formation and subsequent outbreaks.

Comparatively, oospore generation in Oomycetes contrasts with spore formation in true fungi, which often involves structures like asci or basidia. While fungal spores are typically haploid and produced through meiosis, oospores are diploid and result from a fertilization event. This distinction not only highlights evolutionary divergence but also explains why Oomycetes are classified separately from true fungi. Despite these differences, both groups rely on spores as survival mechanisms, showcasing convergent evolutionary strategies in the microbial world.

In conclusion, oospore generation in Oomycetes is a fascinating example of adaptation and survival. By focusing on the interplay between oogonia and antheridia, we gain insights into the reproductive biology of these organisms and their impact on ecosystems and agriculture. Whether you're a researcher, farmer, or enthusiast, appreciating this process equips you with the knowledge to mitigate their negative effects while acknowledging their ecological role. After all, even water molds have a story worth telling.

Understanding Spores: Mitotic or Meiotic? A Comprehensive Exploration

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Sexual spores in fungi are produced through a process called karyogamy, where two compatible haploid nuclei fuse to form a diploid zygote. This zygote then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, such as ascospores in Ascomycetes or basidiospores in Basidiomycetes.

Sexual spore formation in fungi involves specialized structures like ascocarps (e.g., asci in Ascomycetes) or basidiocarps (e.g., basidia in Basidiomycetes). These structures provide the environment for nuclear fusion, meiosis, and spore development.

No, not all fungi produce sexual spores. Some fungi are asexual or have lost the ability to undergo sexual reproduction due to evolutionary adaptations. Others may only produce sexual spores under specific environmental conditions or when compatible mates are present.