Spores, seeds, and cones are distinct reproductive structures found in different plant groups, each adapted to specific environments and life cycles. Spores are microscopic, unicellular or multicellular structures produced by non-seed plants like ferns and fungi, primarily for asexual reproduction and dispersal. They are lightweight and can travel long distances through wind or water, allowing plants to colonize new areas quickly. Seeds, on the other hand, are characteristic of flowering plants (angiosperms) and gymnosperms like conifers, and they contain an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat, enabling them to survive harsh conditions and grow into new plants. Cones, specifically found in gymnosperms such as pines and spruces, are woody structures that house and protect seeds or reproductive cells, facilitating pollination and seed dispersal in wind-dependent environments. While spores rely on simplicity and abundance for survival, seeds and cones emphasize protection and resource allocation, reflecting the evolutionary strategies of their respective plant groups.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Structure | Spores: Single-celled or simple multicellular structures, often microscopic. Seeds: Embryonic plants enclosed in a protective coat, typically larger than spores. Cones: Woody or scaly structures containing seeds or spores, depending on the plant type. |

| Reproduction | Spores: Asexual or sexual reproduction, dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Seeds: Sexual reproduction, formed from fertilized ovules. Cones: Primarily involved in sexual reproduction, housing seeds or spores. |

| Protection | Spores: Minimal protection, rely on numbers for survival. Seeds: Protected by a seed coat, often with stored nutrients (endosperm). Cones: Provide physical protection for seeds or spores within their scales. |

| Dispersal | Spores: Lightweight and easily dispersed over long distances. Seeds: Dispersed via wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms (e.g., pods). Cones: Typically remain on the plant, with seeds or spores dispersed individually. |

| Plant Type | Spores: Produced by ferns, mosses, fungi, and some non-seed plants. Seeds: Produced by angiosperms (flowering plants) and gymnosperms (e.g., pines). Cones: Produced by gymnosperms (e.g., conifers) and some primitive plants. |

| Development | Spores: Develop into new individuals directly or via a gametophyte stage. Seeds: Develop into new plants after germination, bypassing the gametophyte stage. Cones: Develop to mature and release seeds or spores at specific times. |

| Size | Spores: Microscopic to a few millimeters. Seeds: Vary widely, from tiny (e.g., orchids) to large (e.g., coconuts). Cones: Range from small (e.g., juniper) to large (e.g., pine cones). |

| Longevity | Spores: Short-lived, dependent on environmental conditions. Seeds: Can remain dormant for years or even centuries. Cones: Durable, often persisting on the plant for extended periods. |

| Nutrient Storage | Spores: No stored nutrients, rely on immediate environment. Seeds: Contain stored nutrients (endosperm) to support early growth. Cones: Do not store nutrients; seeds within cones may have stored nutrients. |

| Complexity | Spores: Simple, often lacking complex structures. Seeds: Complex, with embryo, stored nutrients, and protective layers. Cones: Structurally complex, with scales or bracts protecting reproductive parts. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dispersal Methods: Spores are wind-dispersed, while seeds use animals, wind, or water, and cones rely on wind

- Structure Differences: Spores are microscopic cells; seeds contain embryos; cones are protective woody structures

- Reproductive Role: Spores are for asexual reproduction; seeds are for sexual reproduction; cones house seeds

- Plant Types: Spores are from ferns and fungi; seeds from angiosperms; cones from gymnosperms

- Survival Strategies: Spores survive harsh conditions; seeds have stored food; cones protect seeds from predators

Dispersal Methods: Spores are wind-dispersed, while seeds use animals, wind, or water, and cones rely on wind

Spores, seeds, and cones are nature's ingenious solutions for plant reproduction, but their dispersal methods reveal distinct strategies shaped by evolution. Spores, typically produced by ferns, fungi, and some plants, are lightweight and microscopic, designed for wind dispersal. This method allows them to travel vast distances with minimal energy investment, ensuring colonization of new habitats even in barren environments. For instance, a single fern can release millions of spores, each capable of growing into a new plant if conditions are favorable. This efficiency makes spores ideal for species thriving in unpredictable or sparse ecosystems.

Seeds, on the other hand, employ a more versatile approach, utilizing animals, wind, or water for dispersal. Plants like dandelions rely on wind to carry their feathery seeds, while others, such as apples or berries, entice animals with edible fruits. Once consumed, the seeds pass through the animal’s digestive system and are deposited in new locations, often with natural fertilizer. Water dispersal is seen in coconut seeds, which can float across oceans to reach distant islands. This diversity in methods ensures seeds can adapt to various environments, increasing their chances of survival and germination.

Cones, characteristic of coniferous trees like pines and spruces, depend primarily on wind for dispersal. When cones mature and dry out, they open to release seeds, which are often winged to aid in wind travel. This strategy is particularly effective in forested areas where wind currents can carry seeds to open ground or gaps in the canopy. However, cones’ reliance on wind limits their dispersal range compared to seeds, making them more localized in their reproductive reach. This specialization reflects the stable, long-lived nature of coniferous forests.

To maximize dispersal success, plants have evolved specific adaptations. For example, spore-producing plants often grow in elevated or exposed locations to catch wind currents. Seed-bearing plants may develop hooks or barbs to attach to animal fur, while others produce buoyant structures for water travel. Cones, meanwhile, are timed to release seeds during windy seasons, ensuring optimal dispersal. Understanding these methods can inform conservation efforts, such as planting spore-producing species in windy areas or protecting animal pathways for seed dispersal.

In practical terms, gardeners and ecologists can mimic these natural processes. For spore-based plants, placing them in open, breezy spots enhances dispersal. Seed-dispersing plants benefit from proximity to wildlife corridors or water bodies. Coniferous trees should be planted in groups to create wind corridors, aiding cone dispersal. By aligning cultivation practices with these methods, we can support plant reproduction and ecosystem health, ensuring biodiversity thrives in both natural and managed environments.

How to Register an EA Account for Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Structure Differences: Spores are microscopic cells; seeds contain embryos; cones are protective woody structures

Spores, seeds, and cones represent distinct reproductive strategies in the plant kingdom, each with unique structural adaptations. Spores, for instance, are microscopic cells, often measuring between 10 to 50 micrometers in diameter. This diminutive size allows them to be dispersed over vast distances by wind or water, a critical advantage for non-vascular plants like ferns and mosses. In contrast, seeds are significantly larger, typically ranging from 1 to 100 millimeters, as they house an embryo, nutrient storage tissues, and a protective coat. Cones, on the other hand, are macroscopic structures composed of woody scales that shield seeds or spores, providing a durable barrier against environmental stressors.

Consider the practical implications of these structural differences. Spores, due to their size, can colonize new habitats rapidly but require specific conditions to germinate. Gardeners cultivating ferns, for example, must maintain high humidity and consistent moisture to ensure spore viability. Seeds, with their embedded embryos and nutrient reserves, offer a higher chance of successful germination, making them ideal for agricultural purposes. A single tomato seed, containing all the genetic material and energy needed for initial growth, can produce a plant yielding dozens of fruits. Cones, such as those of pine trees, serve as long-term protective capsules, often opening only under specific environmental cues like heat or dryness, ensuring seed dispersal at optimal times.

From an evolutionary perspective, these structures reflect adaptations to diverse environments. Spores, being lightweight and numerous, are well-suited for colonizing unstable or nutrient-poor habitats. Seeds, with their complex internal structures, represent a more advanced reproductive strategy, enabling plants to survive dormancy and thrive in competitive ecosystems. Cones, as woody structures, provide mechanical protection and regulated seed release, crucial for coniferous trees in temperate and boreal forests. For instance, the cones of lodgepole pines require intense heat, such as from forest fires, to open and release seeds, ensuring regeneration after disturbances.

To illustrate these differences, imagine a comparative experiment. Place fern spores, sunflower seeds, and pine cones in identical environments with controlled light, water, and temperature. The spores would germinate quickly but produce fragile gametophytes dependent on moisture. The sunflower seeds would sprout robust seedlings, utilizing stored nutrients for rapid growth. The pine cones would remain dormant, their seeds protected until external triggers initiate opening. This experiment highlights how structural differences dictate survival strategies, from the ephemeral nature of spores to the resilience of seeds and the fortitude of cones.

In practical applications, understanding these structures informs horticulture, conservation, and forestry. For spore-bearing plants, creating a humid microclimate with peat moss or misting systems enhances germination rates. Seed-saving enthusiasts can store seeds in cool, dry conditions to prolong viability, while gardeners can use stratification techniques to mimic natural dormancy-breaking processes. For cone-bearing trees, controlled burns or mechanical treatments can simulate natural triggers for seed release, aiding reforestation efforts. By leveraging these structural differences, we can optimize plant propagation and ecosystem restoration, ensuring biodiversity and sustainability.

Can Steam Mops Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home?

You may want to see also

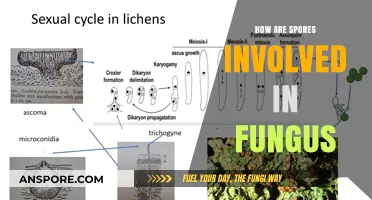

Reproductive Role: Spores are for asexual reproduction; seeds are for sexual reproduction; cones house seeds

Spores and seeds, though both reproductive structures, serve fundamentally different purposes in the plant kingdom. Spores are the champions of asexual reproduction, allowing plants like ferns and mushrooms to propagate without the need for a partner. These microscopic, single-celled units are produced in vast quantities and dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it can develop into a new organism genetically identical to its parent. This method ensures rapid colonization of favorable habitats but limits genetic diversity, making spore-producing plants more vulnerable to environmental changes.

In contrast, seeds are the product of sexual reproduction, a process that combines genetic material from two parent plants. This fusion occurs through pollination, where pollen from the male reproductive organ fertilizes the female ovule. The resulting seed contains a miniature plant (embryo) encased in a protective coat, often with stored nutrients to support early growth. Seeds are larger and more complex than spores, requiring more energy to produce but offering significant advantages. The genetic diversity introduced through sexual reproduction enhances a plant’s ability to adapt to new conditions, increasing its long-term survival prospects.

Cones, primarily associated with coniferous trees like pines and spruces, play a unique role in this reproductive landscape. They are not reproductive units themselves but rather protective structures that house seeds. Cones develop from modified leaves and contain ovules that, once fertilized, mature into seeds. The cone’s design—with scales that open and close in response to environmental conditions—facilitates seed dispersal while shielding them from predators and harsh weather. This dual function of protection and dispersal underscores the cone’s critical role in ensuring the next generation’s success.

Understanding these distinctions is crucial for horticulture, conservation, and even home gardening. For instance, gardeners propagating ferns should prioritize creating humid, shaded environments to encourage spore germination, while those growing conifers must consider the timing of cone opening to collect viable seeds. Educators can use these examples to illustrate the diversity of reproductive strategies in nature, fostering a deeper appreciation for plant biology. By recognizing the unique roles of spores, seeds, and cones, we can better support the plants that sustain our ecosystems.

Does Yeast Reproduce by Spores? Unraveling the Mysteries of Yeast Reproduction

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Plant Types: Spores are from ferns and fungi; seeds from angiosperms; cones from gymnosperms

Plants reproduce in diverse ways, each tailored to their evolutionary niche. Spores, the reproductive units of ferns and fungi, are lightweight, single-celled structures designed for wind dispersal. Ferns release spores from the undersides of their fronds, while fungi disperse them through gills or pores. These spores require moisture to germinate, making them well-suited for damp environments. Unlike seeds, spores lack stored nutrients and develop into a gametophyte stage before producing the next generation. This method thrives in shaded, humid habitats where ferns and fungi dominate.

Seeds, in contrast, are the hallmark of angiosperms (flowering plants). Encased in protective coats, seeds contain an embryo and stored food reserves, ensuring survival in harsh conditions. Angiosperms rely on pollinators like bees or wind to transfer pollen, leading to fertilization and seed formation. This advanced reproductive strategy allows angiosperms to colonize diverse ecosystems, from deserts to rainforests. Seeds’ ability to remain dormant for years gives them a competitive edge over spore-producing plants in unpredictable environments.

Cones, the reproductive structures of gymnosperms (e.g., pines, spruces), bridge the gap between spores and seeds. Cones produce naked seeds, unprotected by ovaries, and rely on wind for pollination. Male cones release pollen, which fertilizes ovules in female cones, eventually developing into seeds. This method is efficient in open, windy habitats where gymnosperms thrive. While less protected than angiosperm seeds, gymnosperm seeds are still more resilient than spores, enabling their success in temperate and boreal forests.

Understanding these reproductive strategies reveals the adaptability of plant types. For gardeners, knowing these differences can guide cultivation: ferns prefer shade and moisture, angiosperms benefit from pollinator-friendly practices, and gymnosperms thrive in well-drained, sunny areas. For educators, this knowledge offers a clear framework to teach plant diversity. Each method—spore, seed, or cone—reflects a unique evolutionary solution to the challenge of survival and propagation in distinct environments.

Do I Still Have C. Diff Spores? Understanding Persistence and Risks

You may want to see also

Survival Strategies: Spores survive harsh conditions; seeds have stored food; cones protect seeds from predators

Spores, seeds, and cones each employ distinct survival strategies tailored to their environments and reproductive needs. Spores, produced by plants like ferns and fungi, are lightweight and resilient, designed to endure extreme conditions such as drought, heat, and cold. Their small size and tough outer walls allow them to remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. For instance, fungal spores can survive in soil for decades, only sprouting when moisture and temperature align. This adaptability ensures their species’ continuity even in unpredictable habitats.

Seeds, on the other hand, are nature’s time capsules, equipped with stored food reserves to nourish the emerging seedling until it can photosynthesize. This internal energy source, often in the form of endosperm or cotyledons, is crucial for survival in nutrient-poor soils or shaded environments. Consider the coconut seed, which can float across oceans and sustain the developing plant with its rich endosperm until it reaches land and takes root. This strategy contrasts sharply with spores, which rely on external conditions rather than internal resources.

Cones, primarily associated with coniferous trees like pines and spruces, serve as protective fortresses for seeds. Their woody, scaled structure shields seeds from predators such as birds and squirrels, while also regulating seed release in response to environmental cues like fire or heat. For example, some pine cones remain closed until a forest fire triggers them to open, dispersing seeds into freshly cleared, nutrient-rich soil. This dual role of protection and timed dispersal highlights cones’ unique contribution to plant survival.

Comparing these strategies reveals a spectrum of survival tactics. Spores prioritize endurance, seeds focus on self-sufficiency, and cones emphasize defense and timing. Each approach reflects the specific challenges faced by the plant, whether it’s surviving harsh climates, establishing roots in competitive environments, or safeguarding the next generation from predators. Understanding these differences offers insights into the evolutionary ingenuity of plants and their ability to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Practical applications of these strategies can inspire human innovation. For instance, spore-like technologies could enhance food preservation in extreme conditions, while seed-inspired designs might improve energy storage in remote devices. Cones’ protective mechanisms could inform packaging solutions for fragile items. By studying these natural survival strategies, we can develop sustainable solutions that mimic the efficiency and resilience of the plant world.

Do Fungal Spores Contain DNA? Unveiling the Genetic Secrets Within

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are microscopic, unicellular reproductive units produced by non-seed plants like ferns and fungi, while seeds are mature, multicellular structures containing an embryo, found in flowering plants and gymnosperms. Cones are specialized structures in gymnosperms (e.g., pines) that produce and protect seeds or spores.

Yes, but through different processes. Spores germinate into gametophytes, which produce gametes for sexual reproduction. Seeds develop into new plants directly when conditions are favorable. Cones facilitate seed or spore development and dispersal but do not grow into plants themselves.

Spores are produced by ferns, mosses, and fungi. Seeds are produced by angiosperms (flowering plants) and gymnosperms (e.g., conifers). Cones are exclusive to gymnosperms like pines, spruces, and firs.

Spores are typically unprotected and rely on numbers for successful dispersal. Seeds are protected by a seed coat and often have stored nutrients. Cones provide physical protection for seeds or spores, shielding them from predators and harsh conditions.

Spores are involved in the alternation of generations, a form of sexual reproduction in non-seed plants. Seeds result from sexual reproduction in seed plants. Cones facilitate sexual reproduction by housing male and female reproductive structures in gymnosperms.