Fungal spores and bacterial endospores share striking similarities as survival structures, both serving as highly resistant forms that enable their respective organisms to endure harsh environmental conditions. While fungal spores are reproductive units designed for dispersal and colonization, bacterial endospores are dormant, resilient forms that protect the bacterial genome during adverse conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or chemical exposure. Both structures possess robust outer layers that shield their genetic material, with fungal spores often having cell walls composed of chitin and bacterial endospores featuring a multilayered coat including a spore coat and exosporium. Additionally, both are metabolically inactive in their dormant state, allowing them to persist for extended periods until favorable conditions return. These similarities highlight convergent evolutionary strategies in fungi and bacteria to ensure survival in challenging environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Resistance to Environmental Stress | Both fungal spores and bacterial endospores are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions, including heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals. |

| Dormancy | Both structures can remain dormant for extended periods, allowing them to survive until favorable conditions return. |

| Small Size | Fungal spores and bacterial endospores are typically small, facilitating dispersal by air, water, or other means. |

| Protective Coatings | Both are encased in protective layers (e.g., spore walls in fungi and exosporium in endospores) that enhance their durability. |

| Metabolic Inactivity | During dormancy, both structures exhibit minimal metabolic activity, conserving energy and resources. |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Both are adapted for efficient dispersal, aiding in colonization of new environments. |

| Genetic Material Protection | Both structures safeguard their genetic material (DNA) from damage, ensuring survival and future germination. |

| Role in Survival | Both serve as survival structures, enabling the organism to persist through adverse conditions. |

| Germination Ability | Both can germinate under suitable conditions, resuming growth and metabolic activity. |

| Ecological Importance | Both play crucial roles in the life cycles and ecological success of fungi and bacteria, respectively. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Resistance Mechanisms: Both fungal spores and bacterial endospores survive harsh conditions like heat, desiccation, and chemicals

- Dormancy State: Each can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions return for growth

- Structural Protection: Thick, durable cell walls shield genetic material from environmental damage in both types

- Dispersal Strategies: Spores and endospores are lightweight, aiding wind or water dispersal to new habitats

- Survival Purpose: Both serve as survival structures, ensuring species persistence during unfavorable environmental conditions

Resistance Mechanisms: Both fungal spores and bacterial endospores survive harsh conditions like heat, desiccation, and chemicals

Fungal spores and bacterial endospores are nature's answer to survival in extreme environments, employing remarkably similar yet distinct strategies to withstand conditions that would destroy most life forms. Both structures are dormant, highly resistant cells that can persist for years, even centuries, in adverse conditions such as high temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. This resilience is not just a coincidence but a result of specialized adaptations that allow them to endure until conditions become favorable for growth and reproduction.

One key mechanism of resistance is the presence of a thick, protective cell wall. In fungal spores, this wall is often composed of chitin and other polysaccharides, providing a robust barrier against mechanical damage and chemical assault. Bacterial endospores, on the other hand, have a multilayered structure, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and a spore coat made of keratin-like proteins, which together offer exceptional resistance to heat, radiation, and desiccation. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* endospores can survive temperatures up to 121°C for 20 minutes, a feat achieved through the spore coat’s ability to prevent water loss and denaturation of internal proteins.

Another shared trait is the reduction of metabolic activity to near-zero levels during dormancy. Both fungal spores and bacterial endospores minimize water content and accumulate protective molecules like trehalose, a sugar that stabilizes cellular structures during dehydration. Trehalose acts as a "water replacement," preserving membranes and proteins in a glass-like state that resists damage. This metabolic shutdown is so effective that fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus niger*, can survive in arid deserts, while bacterial endospores, like those of *Clostridium botulinum*, can persist in soil for decades, waiting for the right conditions to reactivate.

Chemically, both types of spores are resistant to disinfectants and antibiotics due to their impermeable outer layers. For example, fungal spores of *Candida albicans* can withstand exposure to common antifungal agents like fluconazole, while bacterial endospores are notoriously resistant to antibiotics such as penicillin. This resistance poses challenges in medical and industrial settings, where complete sterilization often requires extreme measures like autoclaving at 121°C and 15 psi for 15–30 minutes, specifically to target these resilient structures.

Practical tips for dealing with these resistant forms include using spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine bleach, which can penetrate the protective layers, and ensuring thorough heat treatment for sterilization. For example, in food preservation, canning at temperatures above 100°C for extended periods is essential to destroy bacterial endospores, while in healthcare, proper autoclave protocols are critical to prevent contamination. Understanding these resistance mechanisms not only highlights the ingenuity of microbial survival strategies but also informs effective strategies to combat them in various applications.

Can Spores Develop into Independent Individuals? Exploring the Science

You may want to see also

Dormancy State: Each can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions return for growth

Both fungal spores and bacterial endospores exhibit a remarkable ability to enter a state of dormancy, a survival strategy that allows them to withstand harsh environmental conditions. This dormant phase is not merely a passive state but a highly regulated process, ensuring their longevity and resilience. When faced with adverse conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient scarcity, these microorganisms activate specific genetic programs to initiate dormancy.

The Art of Survival: A Comparative Analysis

Fungal spores and bacterial endospores employ distinct yet equally effective mechanisms to achieve dormancy. Fungi, for instance, produce spores with thickened cell walls, often containing storage compounds like lipids and carbohydrates. These spores can remain viable for years, even decades, in a dry, metabolically inactive state. A notable example is the fungus *Aspergillus*, whose spores can survive in extreme environments, including the harsh conditions of space, as demonstrated in a 2019 study by the European Space Agency.

Practical Implications and Strategies

Understanding this dormancy state has practical applications in various fields. In agriculture, for instance, knowing the dormant capabilities of fungal spores can inform strategies to control crop diseases. Farmers can implement measures to prevent spore germination during favorable conditions, such as using fungicides at specific growth stages or employing crop rotation to disrupt the spore's life cycle. Similarly, in the food industry, controlling humidity and temperature can prevent the germination of bacterial endospores, ensuring food safety.

A Tale of Two Microorganisms: Unlocking Dormancy

The process of awakening from dormancy is equally fascinating. For bacterial endospores, germination is triggered by specific nutrients, often amino acids or sugars, which activate enzymes to break down the endospore's protective layers. In fungi, spores may require specific environmental cues, such as changes in pH, moisture, or temperature, to initiate germination. This precise control over dormancy and germination ensures that these microorganisms only invest energy in growth when conditions are optimal.

Maximizing Dormancy for Preservation and Control

To harness the power of dormancy, consider the following:

- Preservation Techniques: In biotechnology, inducing dormancy in microorganisms can preserve cultures for extended periods. This is particularly useful for maintaining diverse microbial collections or storing genetically modified strains.

- Environmental Control: In industrial settings, managing environmental factors can prevent unwanted microbial growth. For instance, maintaining low humidity and temperature in storage facilities can inhibit spore germination, reducing the risk of contamination.

- Medical Applications: Understanding dormancy mechanisms can contribute to developing strategies against bacterial infections. By targeting the germination process, researchers can explore novel antimicrobial approaches, especially against spore-forming pathogens like Clostridium difficile.

In summary, the dormancy state of fungal spores and bacterial endospores is a sophisticated survival mechanism, offering insights into microbial resilience. By studying and applying this knowledge, we can develop practical solutions in agriculture, food safety, and medicine, ultimately leveraging the power of dormancy for human benefit.

Does Anyone Really Read Barstool Sports? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

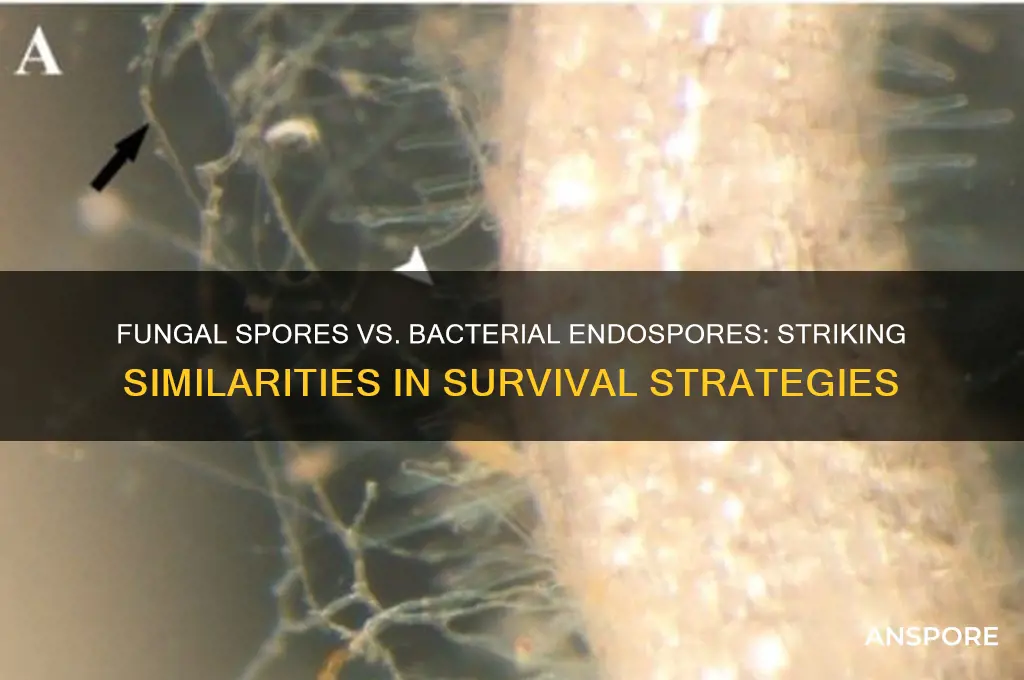

Structural Protection: Thick, durable cell walls shield genetic material from environmental damage in both types

Both fungal spores and bacterial endospores employ a remarkable strategy to ensure their survival in harsh conditions: they fortify their genetic material with thick, durable cell walls. These walls act as a protective armor, shielding the delicate DNA from environmental threats such as desiccation, extreme temperatures, and chemical damage. This structural defense is a key adaptation that allows these microorganisms to persist in environments where other life forms would perish.

Consider the composition of these cell walls. In fungi, the spore walls are often enriched with chitin, a robust polysaccharide that provides rigidity and resistance to degradation. Similarly, bacterial endospores contain a layer called the cortex, which is rich in peptidoglycan, a sturdy polymer that confers additional strength. Both structures are designed to withstand mechanical stress and enzymatic breakdown, ensuring the genetic material remains intact even under adverse conditions.

The thickness of these walls is not arbitrary; it is precisely tuned to balance protection with functionality. For instance, fungal spore walls can be several micrometers thick, providing a formidable barrier without compromising the spore’s ability to germinate when conditions improve. Bacterial endospores take this a step further, with a multilayered structure that includes an outer exosporium and an inner spore coat, each contributing to the overall durability. This layered approach ensures that even if one layer is breached, the genetic material remains protected.

Practical applications of this structural protection are evident in industries such as agriculture and medicine. Fungal spores, with their resilient walls, are used in biofungicides to control plant diseases, as they can survive on leaves and in soil until needed. Bacterial endospores, particularly those of *Bacillus* species, are employed in probiotics and vaccines due to their ability to remain viable during storage and transit. Understanding these protective mechanisms allows scientists to harness their potential for various biotechnological purposes.

To maximize the benefits of these structures, consider the following tips: when storing fungal spores or bacterial endospores for long-term use, maintain a low-humidity environment to prevent wall degradation. For laboratory cultures, avoid exposure to harsh chemicals or extreme temperatures that could compromise the protective layers. By respecting the natural defenses of these microorganisms, you can ensure their longevity and effectiveness in both research and practical applications.

Is Spore Available for Xbox 360? Compatibility and Alternatives Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dispersal Strategies: Spores and endospores are lightweight, aiding wind or water dispersal to new habitats

Spores and endospores, though produced by distinct organisms—fungi and bacteria, respectively—share a critical trait: their lightweight nature. This characteristic is no accident. It is a key adaptation that facilitates their primary function: dispersal. Weighing mere micrograms, these structures are easily carried by wind currents or water flow, allowing them to travel vast distances and colonize new habitats. This dispersal strategy is essential for survival, enabling both fungi and bacteria to exploit resources in diverse environments and ensuring their persistence across changing conditions.

Consider the mechanics of wind dispersal. Fungal spores, often produced in vast quantities, are released into the air from structures like gills or asci. Their small size and low mass allow them to remain suspended for extended periods, increasing the likelihood of being carried far from their origin. Similarly, bacterial endospores, though typically formed in soil or aquatic environments, can be aerosolized by disturbances like plowing or wave action. Once airborne, both spores and endospores act as microscopic explorers, seeking out new substrates where they can germinate and thrive. For instance, a single fungal spore can travel kilometers before landing on a decaying log, while an endospore might drift into a nutrient-rich puddle, ready to revive under favorable conditions.

Water dispersal follows a parallel logic. Fungal spores, particularly those of aquatic or semi-aquatic species, are often hydrophobic, allowing them to float on water surfaces until they encounter a suitable substrate. Bacterial endospores, with their durable coats, can withstand the rigors of water transport, including exposure to UV radiation and predators. This dual adaptability—to both wind and water—maximizes their chances of reaching environments where they can germinate. For example, *Aspergillus* spores may float down a river to colonize damp grain stores, while *Bacillus* endospores might be carried by rainwater into soil cracks, awaiting the moisture needed to reactivate.

Practical implications of this dispersal strategy are significant. In agriculture, understanding how fungal spores travel helps in managing crop diseases; for instance, spacing plants to reduce humidity can limit spore transmission. Similarly, knowledge of endospore dispersal aids in controlling bacterial contamination in water systems, where filtration and UV treatment can intercept airborne or waterborne endospores. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms or studying bacteria, mimicking natural dispersal conditions—such as using fans to simulate wind or misting to simulate rain—can enhance success rates in controlled environments.

In essence, the lightweight design of spores and endospores is a masterclass in biological efficiency. By leveraging natural forces like wind and water, these structures ensure their producers’ genetic continuity across time and space. Whether in a forest, a laboratory, or a farm, recognizing and respecting this dispersal strategy is key to both harnessing and managing these microscopic travelers.

Ozone's Power: Can It Effectively Eliminate C. Diff Spores?

You may want to see also

Survival Purpose: Both serve as survival structures, ensuring species persistence during unfavorable environmental conditions

Fungi and bacteria, though distinct in many ways, share a remarkable survival strategy: the production of resilient structures designed to endure harsh conditions. Fungal spores and bacterial endospores are prime examples of nature’s ingenuity in ensuring species continuity when environments turn hostile. Both are dormant, highly resistant forms that can persist for years, even decades, until conditions improve. This shared purpose highlights a convergent evolutionary solution to the challenge of survival in unpredictable ecosystems.

Consider the lifecycle of a fungus. When nutrients are scarce or temperatures extreme, fungi produce spores—lightweight, often airborne structures that can travel vast distances. Similarly, bacteria form endospores, which are metabolically inactive and encased in a protective layer, allowing them to withstand desiccation, radiation, and extreme temperatures. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the bacterium responsible for anthrax, can survive in soil as an endospore for centuries. Fungi like *Aspergillus* produce spores that remain viable in arid environments, waiting for moisture to trigger germination. Both mechanisms illustrate a strategic retreat into dormancy, a pause in active life until the environment becomes hospitable again.

The resilience of these structures is not just a passive trait but an active adaptation. Fungal spores have thick cell walls composed of chitin, a material resistant to degradation, while bacterial endospores possess a cortex layer rich in dipicolinic acid, which stabilizes DNA and proteins during dormancy. These features enable them to survive conditions that would destroy their active counterparts, such as UV radiation, extreme pH, and high pressure. For practical purposes, this means that sterilizing environments contaminated with spores or endospores requires extreme measures—autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes, for example, is necessary to ensure complete destruction.

From an ecological perspective, this survival strategy has profound implications. It allows fungi and bacteria to colonize diverse habitats, from the deepest oceans to arid deserts, and even outer space. NASA experiments have shown that both fungal spores and bacterial endospores can survive the harsh conditions of space, underscoring their adaptability. This resilience also poses challenges in medical and industrial settings, where contamination by spores or endospores can lead to persistent infections or spoilage. Understanding their survival mechanisms is crucial for developing effective sterilization protocols, such as using spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide vapor in healthcare facilities.

In essence, fungal spores and bacterial endospores are nature’s time capsules, preserving life in a state of suspended animation until the future becomes favorable. Their shared survival purpose underscores a fundamental principle of biology: persistence is as critical as proliferation. Whether you’re a microbiologist studying contamination risks or a gardener battling fungal infections in plants, recognizing the tenacity of these structures is key to managing them effectively. By mimicking their resilience in our own preservation technologies, we can ensure the longevity of everything from food supplies to cultural artifacts, drawing inspiration from the smallest yet most enduring forms of life.

Mange Mites and Dog Aggression: Unraveling the Behavioral Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both fungal spores and bacterial endospores serve as survival structures, allowing the organisms to withstand harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical exposure.

Fungal spores are typically formed through asexual or sexual reproduction processes, such as budding or sporulation, while bacterial endospores are formed through a specialized cellular process within a single bacterial cell, often in response to nutrient deprivation.

Yes, both fungal spores and bacterial endospores can remain dormant for long periods, sometimes even centuries, until favorable conditions return, at which point they can germinate and resume growth.