Measuring spores is a critical process in various fields, including microbiology, agriculture, and environmental science, as it helps assess fungal presence, viability, and potential health or ecological impacts. Spores are typically measured using a combination of techniques, such as microscopy for direct visualization and counting, hemocytometers for precise quantification, and flow cytometry for analyzing spore size and viability. In environmental studies, air samplers are employed to collect and quantify airborne spores, while in industrial settings, spore counts are monitored to ensure product quality and safety. Advanced methods like PCR and DNA sequencing are also used to identify specific spore types. Accurate measurement is essential for understanding spore distribution, predicting disease outbreaks, and managing fungal contamination in diverse contexts.

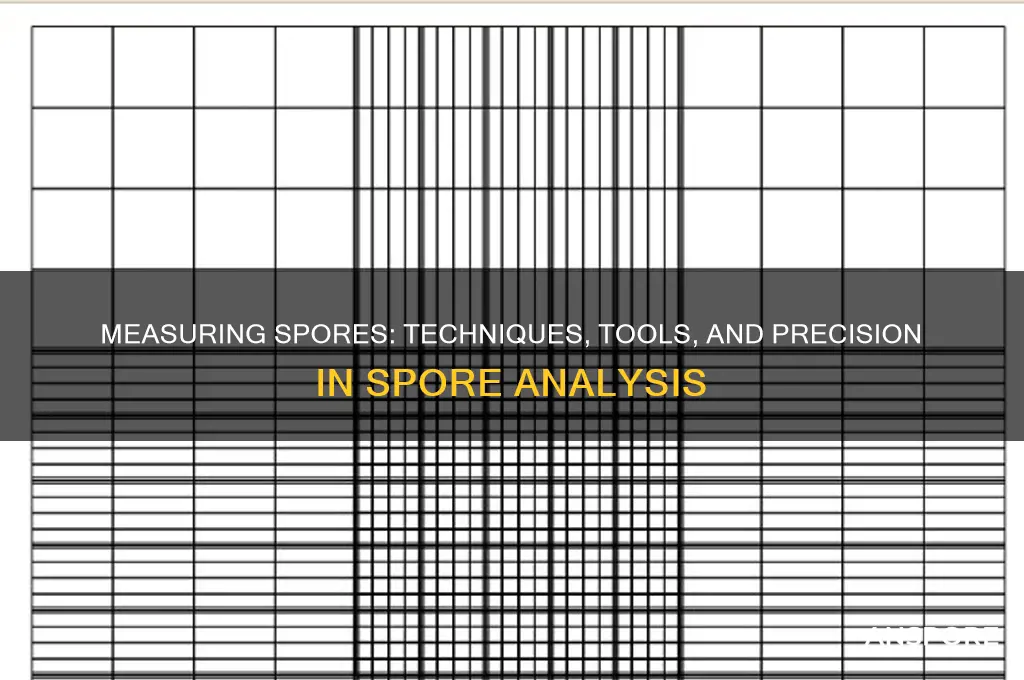

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Measurement Techniques | Light Microscopy, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), Flow Cytometry, Spectrophotometry |

| Size Measurement | Typically ranges from 0.5 to 15 micrometers (μm) in diameter, measured using calibrated microscopes or image analysis software |

| Shape Analysis | Spherical, oval, cylindrical, or irregular shapes, assessed visually or via automated image processing |

| Surface Features | Spore coat thickness, ornamentation (e.g., spines, ridges), and texture, observed under SEM or TEM |

| Viability Assessment | Germination tests, staining (e.g., tetrazolium chloride), or molecular methods (e.g., PCR) to determine living vs. dormant spores |

| Concentration Measurement | Hemocytometer counting, flow cytometry, or quantitative PCR for spore quantification in samples |

| Heat Resistance | Determined by thermal death time (TDT) studies or differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) |

| Desiccation Tolerance | Measured by survival rates after exposure to low humidity or drying conditions |

| Chemical Resistance | Assessed by exposure to disinfectants, solvents, or other chemicals followed by viability testing |

| Genetic Analysis | DNA extraction and sequencing for species identification or genetic diversity studies |

| Environmental Sampling | Air samplers, surface swabs, or soil extracts for spore collection and analysis |

| Standardization | Reference materials (e.g., NIST standards) and calibrated instruments for accurate measurements |

| Data Analysis | Statistical methods, image analysis software, or machine learning algorithms for quantitative characterization |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Microscopy Techniques: Light, electron, and fluorescence microscopy for spore size, shape, and surface detail visualization

- Flow Cytometry: Measuring spore size, density, and viability using light scattering and fluorescence

- Image Analysis Software: Automated tools for quantifying spore dimensions, counts, and morphological features

- Spectroscopic Methods: Using Raman or FTIR spectroscopy to identify spore chemical composition and structure

- PCR and DNA Quantification: Assessing spore concentration via DNA extraction and quantitative PCR techniques

Microscopy Techniques: Light, electron, and fluorescence microscopy for spore size, shape, and surface detail visualization

Spores, with their diverse sizes, shapes, and surface features, require specialized microscopy techniques for accurate visualization and measurement. Light microscopy, the most accessible method, provides a foundational view of spore morphology. Using brightfield or phase-contrast techniques, researchers can measure spore diameter and length with precision down to 0.1 μm, sufficient for many taxonomic and ecological studies. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores, typically 0.5–1.5 μm in diameter, are easily resolved under a 100x objective with oil immersion. However, light microscopy’s diffraction limit restricts resolution to ~200 nm, making it inadequate for finer surface details.

Electron microscopy (EM) overcomes this limitation, offering resolution down to the nanometer scale. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is particularly effective for visualizing spore surface topography, revealing intricate structures like exosporium layers, ridges, and pores. For instance, SEM images of *Clostridium botulinum* spores highlight their distinctive tennis-ball-like surface texture. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) complements SEM by providing internal structural details, such as spore core density and coat thickness. Preparation for EM is labor-intensive, requiring dehydration, critical point drying, and metal coating for SEM, or ultrathin sectioning for TEM, but the unparalleled detail justifies the effort for advanced studies.

Fluorescence microscopy bridges the gap between light and electron microscopy, combining high specificity with sub-micron resolution. By labeling spore components with fluorescent dyes or proteins, researchers can visualize specific structures, such as DNA, proteins, or surface markers. For example, staining *Aspergillus* spores with calcofluor white highlights their cell walls, while GFP-tagged proteins in *Neurospora crassa* spores reveal germination dynamics. Confocal microscopy further enhances this technique by generating optical sections, enabling 3D reconstruction of spore morphology. This method is particularly valuable for live-cell imaging, as it minimizes phototoxicity and allows real-time observation of spore behavior.

Each microscopy technique offers unique advantages for spore measurement, and the choice depends on the research question. Light microscopy is ideal for rapid, cost-effective assessments of spore size and shape. Electron microscopy provides unmatched detail for surface and internal structures, essential for taxonomic or structural studies. Fluorescence microscopy excels in functional analyses, revealing dynamic processes and specific molecular components. Combining these techniques can provide a comprehensive understanding of spore morphology and biology, ensuring accurate measurement and interpretation of spore characteristics. Practical tips include calibrating microscopes with stage micrometers, using appropriate fixation methods to preserve spore integrity, and optimizing staining protocols for fluorescence studies.

Effective Methods to Eliminate Fungal Spores and Prevent Growth

You may want to see also

Flow Cytometry: Measuring spore size, density, and viability using light scattering and fluorescence

Spores, with their remarkable resilience and diversity, present unique challenges for measurement. Traditional methods like microscopy, while effective, can be time-consuming and subjective. Flow cytometry emerges as a powerful alternative, offering rapid, objective, and multi-parametric analysis of spore populations. This technique leverages the principles of light scattering and fluorescence to simultaneously assess spore size, density, and viability, providing a comprehensive understanding of spore characteristics.

The Power of Light Scattering:

Imagine a beam of light encountering a spore. The way this light scatters reveals crucial information. Forward scatter (FSC) measures the size of the spore, as larger particles deflect more light. Side scatter (SSC) indicates internal complexity and granularity, reflecting spore density and surface characteristics. By analyzing these scattering patterns, flow cytometry can differentiate between spores of varying sizes and densities, even within a mixed population.

For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores, known for their robust nature, exhibit distinct FSC and SSC profiles compared to the smaller, less dense spores of *Aspergillus niger*.

Fluorescence: Illuminating Viability:

While light scattering provides structural insights, fluorescence adds a layer of functional information. By staining spores with fluorescent dyes that target specific cellular components, flow cytometry can assess spore viability.

Viability stains like propidium iodide (PI) penetrate compromised cell membranes, binding to DNA and emitting fluorescence. Live spores, with intact membranes, exclude PI, remaining unstained. Dead or damaged spores, however, take up the dye, fluorescing brightly. This simple yet powerful approach allows for rapid quantification of viable spores within a sample.

More sophisticated dyes, like CFDA-SE, can assess metabolic activity, providing a more nuanced view of spore viability.

Practical Considerations and Applications:

Flow cytometry offers several advantages for spore analysis. Its high-throughput capability allows for rapid screening of large spore populations, making it ideal for quality control in industries like food production and biotechnology. The ability to analyze multiple parameters simultaneously provides a comprehensive understanding of spore characteristics, aiding in strain identification and comparative studies.

However, careful optimization is crucial. Choosing the appropriate dyes and staining protocols is essential for accurate results. Instrument settings, such as laser power and detector voltages, need to be calibrated for optimal sensitivity and resolution.

Beyond Measurement: Unlocking Spore Biology:

Flow cytometry's ability to measure spore size, density, and viability simultaneously opens doors to exciting research avenues. It enables the study of spore germination kinetics, the effects of environmental stressors on spore survival, and the development of novel spore-based technologies. By providing a detailed picture of spore populations, flow cytometry empowers researchers to unlock the secrets of these remarkable organisms and harness their potential in various fields.

Algae Spores Fusion: Understanding Diploids Formation in Algal Life Cycles

You may want to see also

Image Analysis Software: Automated tools for quantifying spore dimensions, counts, and morphological features

Spores, with their microscopic size and diverse shapes, present a unique challenge for accurate measurement and analysis. Traditional methods, such as manual counting under a microscope, are time-consuming and prone to human error. This is where image analysis software steps in, revolutionizing spore quantification by offering automated, precise, and efficient solutions.

Example: Imagine needing to assess the spore density of a fungal sample for agricultural research. Manually counting hundreds, if not thousands, of spores on a slide is not only tedious but also subject to fatigue-induced inaccuracies. Image analysis software, equipped with advanced algorithms, can process high-resolution images of the sample, automatically detecting, counting, and measuring individual spores with remarkable speed and consistency.

Analysis: These software tools leverage sophisticated image processing techniques. They employ thresholding to distinguish spores from the background, segmentation to isolate individual spores, and feature extraction to measure parameters like diameter, area, and shape descriptors. Some advanced software even utilizes machine learning algorithms trained on vast datasets of spore images, enabling them to accurately identify and classify different spore types based on their unique morphological characteristics.

Takeaway: Image analysis software transforms spore measurement from a laborious manual task into a streamlined, objective process. This automation not only saves valuable time but also enhances the accuracy and reproducibility of spore analysis, crucial for fields like microbiology, agriculture, and environmental monitoring.

Steps to Utilize Image Analysis Software:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare your spore sample on a microscope slide, ensuring even distribution and minimal clumping.

- Image Acquisition: Capture high-resolution images of the sample using a microscope equipped with a digital camera.

- Software Selection: Choose software suitable for your needs, considering factors like spore type, desired measurements, and budget.

- Image Processing: Load the images into the software and apply appropriate settings for thresholding, segmentation, and feature extraction.

- Data Analysis: Review the software-generated data, including spore counts, size distributions, and morphological parameters.

Cautions: While powerful, image analysis software requires careful consideration. Image quality is paramount; poor lighting, focus, or debris can lead to inaccurate results. Additionally, software settings need to be optimized for each specific spore type and sample preparation method.

Microwave Impact on Spore-Forming Probiotics: Do They Survive the Heat?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spectroscopic Methods: Using Raman or FTIR spectroscopy to identify spore chemical composition and structure

Spores, with their resilient structures and complex chemical compositions, present a unique challenge for identification and analysis. Spectroscopic methods, particularly Raman and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, offer non-destructive, high-resolution techniques to probe their molecular makeup. These methods leverage the interaction of light with matter to generate spectral fingerprints, revealing insights into spore composition and structure.

Raman spectroscopy, for instance, detects vibrational modes of molecules by measuring the inelastic scattering of laser light. Its ability to penetrate biological samples without extensive preparation makes it ideal for analyzing intact spores. By focusing a laser beam on a spore sample, researchers can obtain a Raman spectrum that highlights the presence of biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates. For example, the characteristic peaks around 1000–1600 cm⁻¹ often correspond to C-C and C=C stretching vibrations in spore coats, providing clues about their structural integrity. A practical tip: use a 785 nm laser to minimize fluorescence interference, which can obscure spectral features in biological samples.

In contrast, FTIR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by spore components, producing spectra that reflect functional groups like amides, hydroxyls, and carboxyls. This technique is particularly useful for identifying spore wall components, such as sporopollenin, a biopolymer resistant to degradation. FTIR can also differentiate between spore types based on their unique chemical signatures. For instance, fungal spores often exhibit strong amide I and II bands (1650–1550 cm⁻¹), indicative of protein-rich walls, while bacterial spores may show prominent lipid absorption peaks around 2900 cm⁻¹. To enhance spectral clarity, prepare samples as thin films or use attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessories, which reduce scattering and improve signal-to-noise ratios.

While both techniques offer complementary advantages, their selection depends on the research question. Raman spectroscopy excels in identifying localized chemical variations within spores, making it suitable for studying spore germination or damage. FTIR, on the other hand, provides a broader overview of bulk composition, ideal for classifying spore types or assessing environmental contamination. Combining these methods can yield a comprehensive understanding of spore chemistry and structure, enabling applications in fields like astrobiology, forensics, and biodefense.

A critical consideration is sample preparation and instrument calibration. Spores’ small size and heterogeneous nature require careful handling to ensure representative results. For Raman analysis, mount spores on a glass slide or use a microfluidic device to immobilize them. For FTIR, grinding spores into a fine powder or mixing them with KBr can improve spectral quality. Calibrate instruments using reference materials, such as polystyrene for Raman or polyethylene for FTIR, to account for instrument variability. By mastering these techniques, researchers can unlock the molecular secrets of spores, advancing both fundamental science and practical applications.

Milky Spore and Cicadas: Effective Control or Myth?

You may want to see also

PCR and DNA Quantification: Assessing spore concentration via DNA extraction and quantitative PCR techniques

Spores, with their resilient nature, pose a unique challenge in quantification. Traditional methods like microscopy, while useful, can be time-consuming and lack precision, especially for low concentrations. Here, PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) and DNA quantification emerge as powerful tools, offering a sensitive and specific approach to assessing spore concentration.

Imagine amplifying a specific DNA sequence unique to the spore species of interest, then measuring the amplified product to determine the initial spore count. This is the essence of quantitative PCR (qPCR), a technique revolutionizing spore quantification.

The Process Unveiled:

- DNA Extraction: The journey begins with isolating DNA from the spores. This involves breaking down the spore's tough outer coat using mechanical or chemical methods, followed by purification to obtain pure DNA.

- Primer Design: Specific DNA sequences, called primers, are designed to flank the target region of the spore's DNA. These primers act like molecular bookmarks, guiding the PCR reaction to amplify only the desired sequence.

- QPCR Amplification: The extracted DNA, primers, and other reagents are combined in a reaction mixture. The qPCR machine cycles through repeated heating and cooling steps, exponentially amplifying the target DNA sequence. Fluorescent dyes incorporated into the reaction allow real-time monitoring of the amplification, providing a quantitative measure of the initial DNA concentration.

- Quantification: The qPCR software analyzes the amplification data, generating a standard curve based on known DNA concentrations. This curve allows for the determination of the spore concentration in the original sample by comparing the amplification signal to the standard curve.

Advantages and Considerations:

QPCR offers several advantages over traditional methods:

- Sensitivity: Detects even low spore concentrations, crucial for early detection and risk assessment.

- Specificity: Targets specific spore species, minimizing false positives from other microorganisms.

- Speed: Provides results within hours, enabling rapid decision-making.

However, considerations include:

- DNA Extraction Efficiency: Variations in extraction efficiency can affect accuracy. Standardized protocols and controls are essential.

- Primer Design: Careful primer design is crucial for specificity and efficiency.

- Inhibition: Substances in the sample can inhibit PCR, requiring optimization and potential sample clean-up.

Practical Applications:

QPCR-based spore quantification finds applications in diverse fields:

- Food Safety: Detecting spore-forming pathogens like Bacillus cereus in food products.

- Environmental Monitoring: Assessing spore levels in air, water, and soil for bioremediation or risk assessment.

- Biodefense: Rapid detection of bioterrorism agents like anthrax spores.

PCR and DNA quantification, particularly qPCR, provide a robust and versatile method for assessing spore concentration. While requiring careful optimization and consideration of potential limitations, this technique offers unparalleled sensitivity, specificity, and speed, making it an invaluable tool in various fields where accurate spore quantification is critical.

Are Spores a Fungus? Unraveling the Microscopic Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Common methods include microscopy (light or electron), hemocytometer counting, flow cytometry, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

Microscopy allows for direct visualization and counting of spores, often using a hemocytometer or specialized grids, and can differentiate spore size, shape, and viability.

Flow cytometry measures spore concentration and viability by analyzing light scattering and fluorescence, providing rapid and precise data on spore populations.

Yes, qPCR quantifies spore DNA, offering a highly sensitive method to measure spore concentration, especially in environmental or clinical samples.

Factors include spore clumping, debris in the sample, variability in staining or labeling, and the choice of measurement technique for the specific spore type.