Spores, the reproductive units of many plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are dispersed through various mechanisms to ensure their survival and propagation. This process is crucial for the organism's life cycle, but it does not directly relate to whether the organism is autotrophic or heterotrophic. Autotrophic organisms, like plants, produce their own food through photosynthesis, while heterotrophic organisms, such as fungi and many bacteria, rely on external sources for nutrients. The method of spore dispersal—whether by wind, water, animals, or other means—is a separate biological process that supports the organism's reproductive strategy, regardless of its nutritional mode. Understanding these distinctions helps clarify the roles of spores in both autotrophic and heterotrophic organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, animals, explosive mechanisms (e.g., in fungi), humans |

| Autotrophic or Heterotrophic | Spores themselves are not autotrophic or heterotrophic; they are dormant, metabolically inactive structures. The organism producing the spores (e.g., fungi, plants, bacteria) determines its nutritional mode. |

| Metabolic State of Spores | Dormant, with minimal metabolic activity to survive harsh conditions |

| Function of Spores | Survival and dispersal to new environments |

| Examples of Producers | Fungi (heterotrophic), ferns (autotrophic), bacteria (heterotrophic) |

| Energy Source for Spores | Stored energy reserves (e.g., lipids, starch) until germination |

| Germination Requirement | Favorable conditions (e.g., moisture, temperature, nutrients) |

| Role in Life Cycle | Asexual or sexual reproductive stage, depending on the organism |

| Size and Structure | Small, lightweight, and often protected by a resistant outer layer |

| Longevity | Can remain viable for extended periods, even years, under harsh conditions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Wind Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are lightweight, aiding wind transport over long distances for colonization

- Water Dispersal Methods: Aquatic spores use water currents for movement, ensuring widespread distribution

- Animal-Aided Dispersal: Spores attach to animals, using them as vectors for relocation

- Autotrophic vs. Heterotrophic: Spores are neither; they are dormant, metabolically inactive reproductive units

- Explosive Discharge: Some fungi use forceful mechanisms to eject spores for dispersal

Wind Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are lightweight, aiding wind transport over long distances for colonization

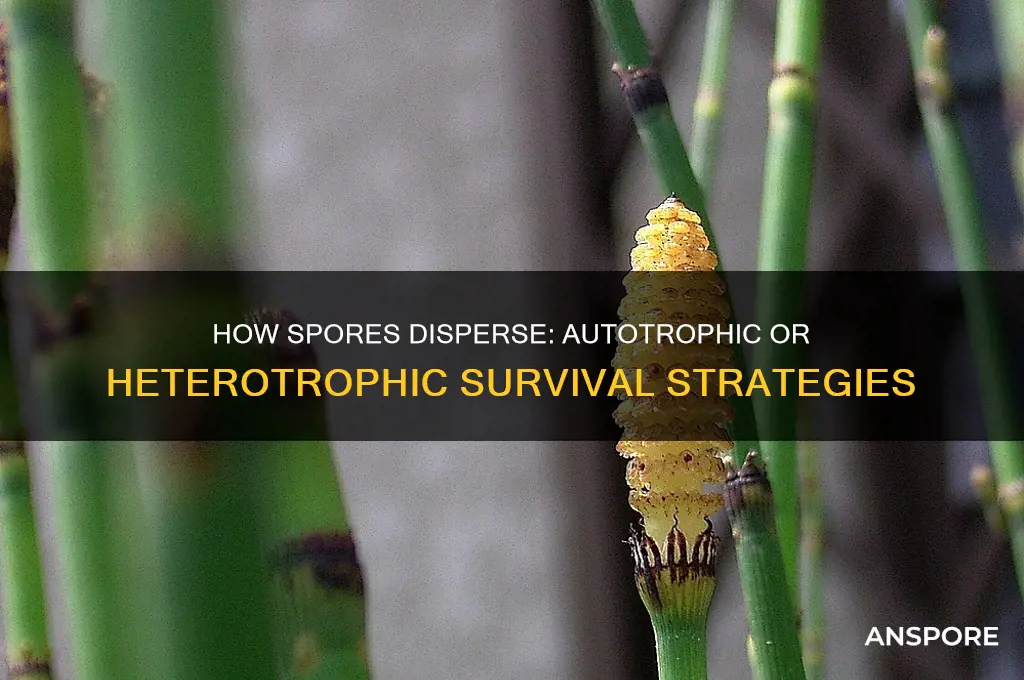

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of many plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are marvels of nature’s design for survival and dispersal. Among the various mechanisms that facilitate their spread, wind dispersal stands out as one of the most efficient and widespread. The key to this success lies in the spores' lightweight structure, which allows them to be carried over vast distances with minimal effort from the environment. This adaptation ensures that even organisms lacking mobility can colonize new habitats, from dense forests to barren landscapes.

Consider the structure of a fern spore, for instance. Measuring just 10 to 50 micrometers in diameter, it is lighter than a grain of pollen. This minuscule size, coupled with a low density, enables spores to remain suspended in air currents for hours or even days. Wind, acting as an invisible carrier, transports these spores across ecosystems, depositing them in locations where they can germinate under favorable conditions. The process is not random but relies on the spores' ability to stay aloft, a feat achieved through their aerodynamic design and the collective behavior of spore clouds.

To maximize wind dispersal, some organisms have evolved specialized structures. Puffballs, a type of fungus, release spores through tiny pores when disturbed, creating a cloud that can be picked up by the slightest breeze. Similarly, the dry, papery wings of certain fern species act as natural sails, catching the wind and carrying spores far beyond their parent plant. These adaptations highlight the interplay between biology and physics, where even the smallest details—like spore shape or release mechanism—can significantly impact dispersal efficiency.

Practical observations of wind dispersal reveal its effectiveness in real-world scenarios. For example, after a volcanic eruption, wind-dispersed spores are often among the first to colonize the ash-covered terrain, playing a critical role in ecosystem recovery. Gardeners and farmers can also harness this mechanism by strategically planting wind-pollinated crops, such as corn or grasses, to ensure cross-pollination. However, this reliance on wind comes with challenges: spores may land in unsuitable environments, and their lightweight nature makes them vulnerable to desiccation or predation.

In conclusion, wind dispersal mechanisms exemplify nature’s ingenuity in overcoming the limitations of immobility. By leveraging lightweight spores, organisms ensure their genetic material travels far and wide, increasing the odds of successful colonization. Understanding these processes not only deepens our appreciation for biological adaptations but also offers practical insights for agriculture, conservation, and ecological restoration. Whether in a laboratory or a field, the study of wind-dispersed spores remains a testament to the delicate balance between form and function in the natural world.

Pollen Grains vs. Spores: Understanding the Key Differences and Similarities

You may want to see also

Water Dispersal Methods: Aquatic spores use water currents for movement, ensuring widespread distribution

Aquatic spores have mastered the art of leveraging water currents for dispersal, a strategy that ensures their survival and proliferation across diverse ecosystems. Unlike terrestrial spores, which rely on wind, animals, or explosive mechanisms, aquatic spores harness the natural flow of water to travel vast distances with minimal energy expenditure. This method is particularly effective in rivers, lakes, and oceans, where currents act as highways for spore transportation. For instance, algae like *Chara* release spores that are carried downstream, colonizing new habitats along the way. This passive yet efficient dispersal mechanism highlights the adaptability of aquatic organisms to their environments.

Consider the lifecycle of *Ulva* (sea lettuce), a green alga commonly found in coastal areas. When mature, *Ulva* releases spores into the water column, where they are swept away by tides and currents. These spores are lightweight and buoyant, allowing them to remain suspended in the water for extended periods. This buoyancy, combined with the relentless movement of water, ensures that spores reach distant shores, intertidal zones, and even deeper waters. The success of this strategy lies in its simplicity: water does the work, and the spores merely need to survive the journey.

However, water dispersal is not without its challenges. Spores must withstand varying salinity levels, temperature fluctuations, and predation during their journey. To mitigate these risks, some aquatic spores have evolved protective coatings or dormancy mechanisms. For example, *Zygospores* of certain freshwater algae have thick walls that protect them from harsh conditions, allowing them to remain viable until they reach a suitable environment. This resilience is crucial, as water currents can be unpredictable, and spores may encounter environments that are temporarily inhospitable.

Practical observations of water dispersal can be made in aquariums or natural water bodies. To study this phenomenon, collect water samples from different locations in a river or lake and examine them under a microscope for spore presence. Note the diversity and concentration of spores, which can vary based on water flow, season, and local flora. For educators or hobbyists, this simple experiment demonstrates the role of water currents in spore distribution and underscores the interconnectedness of aquatic ecosystems.

In conclusion, water dispersal methods exemplify the ingenuity of aquatic spores in utilizing their environment for survival. By relying on water currents, these spores achieve widespread distribution with minimal effort, colonizing new habitats and ensuring genetic diversity. While challenges exist, evolutionary adaptations like protective coatings and dormancy mechanisms enhance their chances of success. Understanding this process not only sheds light on the biology of aquatic organisms but also emphasizes the importance of water ecosystems in sustaining biodiversity.

High Temperatures vs. E. Coli Spores: Can Heat Eliminate the Threat?

You may want to see also

Animal-Aided Dispersal: Spores attach to animals, using them as vectors for relocation

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of many plants, fungi, and some bacteria, rely on diverse mechanisms for dispersal. Among these, animal-aided dispersal stands out as a fascinating strategy. Spores attach to animals, leveraging their movement to relocate across vast distances, often to environments more conducive to growth. This symbiotic relationship highlights the ingenuity of nature, where neither party is directly autotrophic or heterotrophic in this interaction, but rather, both benefit indirectly.

Consider the example of burdock seeds, which have inspired the invention of Velcro. These seeds possess tiny hooks that cling to animal fur, a mechanism known as epizoochory. As animals roam, they inadvertently carry these seeds to new locations, where they can germinate and establish new populations. Similarly, fungal spores often attach to insects, such as beetles or flies, which transport them to fresh substrates. This method ensures that spores reach areas rich in nutrients, enhancing their chances of survival. For instance, certain mushroom spores attach to the legs of ants, which then carry them to decaying wood—an ideal environment for fungal growth.

The effectiveness of animal-aided dispersal lies in its specificity and efficiency. Spores are not randomly scattered but are strategically placed on animals that frequent suitable habitats. This targeted approach increases the likelihood of successful colonization. For example, orchids produce sticky pollen packets called pollinia, which attach to specific pollinators like bees or butterflies. While this primarily aids in pollination, the principle of attachment and transport is analogous to spore dispersal. Such precision ensures that energy invested in spore production is not wasted.

To harness this mechanism in practical applications, such as reforestation or fungal cultivation, consider the following steps: first, identify the target animal species frequenting the desired habitat. Next, design spore carriers (e.g., sticky or hooked structures) that adhere effectively to the animal’s body. Ensure these carriers are non-harmful to the animal and biodegradable. Finally, monitor dispersal patterns to optimize placement and timing. For instance, in reforestation efforts, seeds coated with animal-friendly adhesives could be strategically placed along wildlife trails.

While animal-aided dispersal is a powerful strategy, it is not without challenges. Over-reliance on specific animal species can limit dispersal if those populations decline. Additionally, spores must be durable enough to withstand the journey without losing viability. For example, fungal spores transported by insects must remain intact despite exposure to varying temperatures and humidity. Balancing these factors requires careful planning and experimentation. Despite these challenges, animal-aided dispersal remains a testament to the adaptability of spores, showcasing how heterotrophic organisms (animals) inadvertently support the propagation of autotrophic or saprotrophic species (plants and fungi).

Moss Spores vs. Seeds: Unraveling the Tiny Green Mysteries

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Autotrophic vs. Heterotrophic: Spores are neither; they are dormant, metabolically inactive reproductive units

Spores defy simple categorization as autotrophic or heterotrophic because they exist in a state of dormancy, devoid of active metabolism. Unlike cells engaged in photosynthesis (autotrophic) or organic matter consumption (heterotrophic), spores are metabolically inactive, conserving energy until conditions trigger germination. This quiescent state allows them to withstand harsh environments, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient scarcity, making them highly resilient reproductive units.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern. Spores released from the underside of fronds are dispersed by wind, landing in diverse environments. These spores are not actively photosynthesizing like mature fern plants (autotrophic) nor are they consuming external nutrients like fungi (heterotrophic). Instead, they remain dormant until moisture and warmth signal favorable conditions for growth. This metabolic inactivity is key to their survival strategy, enabling long-distance dispersal and persistence in unfavorable habitats.

To understand this distinction, contrast spores with seeds. While both are reproductive structures, seeds often contain stored nutrients (e.g., endosperm in angiosperms) and may exhibit limited metabolic activity. Spores, however, are minimalistic—typically a single cell with a protective wall—and lack internal energy reserves. Their survival depends entirely on future environmental cues, not on current metabolic processes. This makes them neither autotrophic nor heterotrophic but rather a unique, dormant phase in the life cycle of certain organisms.

Practically, this dormancy has implications for spore dispersal and preservation. For instance, in agriculture, fungal spores are often stored in dry, cool conditions to prolong their viability. Similarly, in biotechnology, spores of bacteria like *Bacillus* are used in probiotics and vaccines due to their stability. Understanding their dormant nature allows for precise control over germination, ensuring spores remain inactive until intentionally activated. This highlights their role as resilient, metabolically neutral units, distinct from both autotrophic and heterotrophic classifications.

In summary, spores occupy a biological niche separate from autotrophic or heterotrophic categories. Their dormancy and metabolic inactivity are adaptations for survival and dispersal, not modes of nutrition. This unique characteristic enables them to endure extreme conditions and disperse widely, making them essential to the life cycles of fungi, plants, and some bacteria. Recognizing spores as neither autotrophic nor heterotrophic but as dormant reproductive units clarifies their ecological and practical significance.

Exploring Bryophytes: Do They Possess Spore Capsules for Reproduction?

You may want to see also

Explosive Discharge: Some fungi use forceful mechanisms to eject spores for dispersal

Fungi have evolved ingenious strategies to disperse their spores, ensuring the survival and propagation of their species. Among these, explosive discharge stands out as a dramatic and highly effective method. Certain fungi, such as those in the genus *Pilobolus*, have developed specialized structures that act like tiny cannons, propelling spores over impressive distances. This mechanism is not just a biological curiosity; it’s a testament to the precision and efficiency of nature’s engineering.

To understand how this works, imagine a microscopic catapult. The fungus builds up pressure within a spore-containing structure called a sporangium. When conditions are right—often triggered by light or moisture—the sporangium ruptures, releasing spores with enough force to travel several centimeters, or even meters, away from the parent organism. For example, *Pilobolus* spores can be ejected at speeds up to 25 meters per second, landing on nearby plants or surfaces where they can germinate. This explosive method ensures spores are not left to disperse passively, increasing their chances of finding new habitats.

The practical implications of this mechanism are worth noting. For gardeners or farmers dealing with fungal infestations, understanding explosive discharge can inform control strategies. Spores ejected forcefully are more likely to colonize new areas quickly, so containment measures must account for this range. Additionally, researchers studying spore dispersal can use high-speed cameras to capture the process, revealing insights into fluid dynamics and biomechanics. This knowledge isn’t just academic; it has applications in fields like bioengineering, where mimicking such mechanisms could inspire new technologies.

Comparatively, explosive discharge is far more efficient than passive dispersal methods, such as wind or water. While passive methods rely on external forces, active mechanisms like this ensure spores are dispersed intentionally and directionally. This is particularly advantageous for fungi in dense environments where competition for space is high. By ejecting spores with force, these fungi bypass the unpredictability of passive dispersal, securing a competitive edge in their ecosystems.

In conclusion, explosive discharge is a remarkable adaptation that showcases the sophistication of fungal biology. It’s a reminder that even the smallest organisms can employ complex strategies to thrive. Whether you’re a scientist, gardener, or simply a curious observer, understanding this mechanism offers valuable insights into the natural world—and perhaps even inspiration for human innovation.

Can Bacteria Form Spores? Unveiling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are dispersed through various mechanisms, including wind, water, animals, and even explosive discharge in some fungi. Wind is the most common method, as spores are often lightweight and can travel long distances.

Organisms that produce spores, such as fungi and some plants, are typically heterotrophic. They obtain nutrients by breaking down organic matter, although some plants (like ferns) are autotrophic, producing their own food through photosynthesis.

Yes, spores serve as a critical means of dispersal and survival for many organisms. They are highly resistant to harsh conditions, allowing them to persist in unfavorable environments until conditions improve for growth and reproduction.