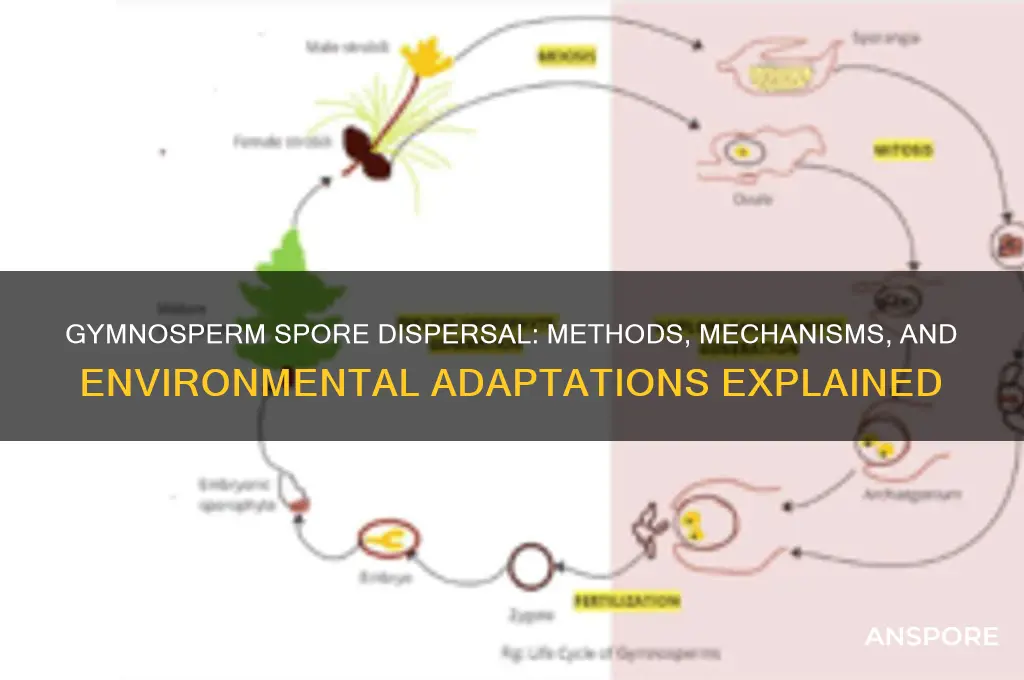

Gymnosperms, a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, primarily reproduce through the dispersal of spores rather than flowers and fruits. Unlike angiosperms, gymnosperms produce naked seeds not enclosed within an ovary, and their spore dispersal mechanisms are closely tied to their life cycle, which involves alternation of generations. In gymnosperms, spores are produced in structures called cones or strobili. Male cones generate microspores, which develop into pollen grains, while female cones produce megaspores that give rise to the female gametophyte. Dispersal of these spores is typically facilitated by wind, as gymnosperms lack specialized structures for animal-mediated dispersal. Pollen grains, being lightweight and often equipped with air sacs or wings, are easily carried by air currents to reach female cones, ensuring fertilization. This wind-dependent dispersal strategy is highly effective for gymnosperms, allowing them to thrive in diverse environments, from dense forests to open landscapes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dispersal Method | Primarily via wind (anemochory) |

| Spore Type | Microspores (male) and megaspores (female) |

| Microspore Dispersal | Released through microsporangia located on the undersides of leaves |

| Megaspore Dispersal | Retained within ovules, which are often located in cones or similar structures |

| Wind Adaptation | Lightweight, small spores with wings or air sacs for efficient dispersal |

| Pollination | Wind-pollinated (no flowers or insects involved) |

| Cone Structure | Cones open to release microspores and expose ovules for pollination |

| Seed Formation | Spores develop into gametophytes within the ovule, leading to seed formation |

| Dispersal Range | Can travel long distances due to wind-driven dispersal |

| Examples of Gymnosperms | Conifers (e.g., pines, spruces), cycads, ginkgo, and gnetophytes |

| Seasonal Timing | Spores are typically dispersed during specific seasons (e.g., spring) |

| Protection Mechanism | Cones provide physical protection for developing spores and seeds |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Wind-mediated spore dispersal mechanisms in gymnosperms

Gymnosperms, unlike their angiosperm counterparts, rely heavily on wind for spore dispersal, a process that hinges on lightweight, aerodynamic structures. Conifers, the most prominent gymnosperms, produce spores within cones, which are designed to catch air currents. Male cones, for instance, are typically smaller and more numerous, releasing vast quantities of pollen grains—each measuring around 20-50 micrometers in diameter—that can travel kilometers when conditions are favorable. This strategy ensures that even if a small fraction of spores reach a female cone, fertilization can occur. The success of this method lies in the sheer volume of spores produced and their ability to remain suspended in air for extended periods.

The anatomy of gymnosperm spores and pollen further enhances wind dispersal. Pollen grains are often spherical and smooth, reducing air resistance, while some species have sac-like structures (saccate pollen) that increase surface area, aiding buoyancy. Female cones, on the other hand, are positioned to intercept these airborne spores. Their exposed ovules and sticky surfaces trap pollen efficiently, a passive yet effective mechanism. This dual adaptation—lightweight pollen and receptive cones—maximizes the chances of successful fertilization in environments where wind is the primary dispersal agent.

Consider the lifecycle of a pine tree to illustrate this mechanism. In spring, male cones release clouds of yellow pollen, which the wind carries to female cones higher up in the canopy. This vertical separation minimizes self-fertilization, promoting genetic diversity. By the following year, fertilized ovules develop into seeds within woody cones, which eventually open to release the next generation. This timed sequence ensures that pollen dispersal occurs when wind conditions are optimal, typically during dry, breezy periods.

While wind-mediated dispersal is efficient, it is not without challenges. Spores may land in unsuitable environments, and reliance on wind limits control over dispersal direction. Gymnosperms mitigate this by producing spores in staggering quantities—a single pine tree can release millions of pollen grains annually. Additionally, some species have evolved cone structures that open and close in response to humidity, releasing spores only under ideal conditions. For gardeners or foresters, understanding this timing can aid in seed collection or pest management, as pollen release often coincides with allergenic spikes.

In practical terms, wind dispersal in gymnosperms offers lessons for conservation and horticulture. Planting conifers in wind corridors can enhance seed spread, while protecting mature trees ensures consistent spore production. For those studying or managing forests, monitoring pollen seasons—typically spring for most conifers—can provide insights into tree health and reproductive success. By mimicking nature’s design, even urban planners can incorporate wind-dispersed species to promote biodiversity in green spaces. This ancient mechanism, refined over millennia, remains a cornerstone of gymnosperm survival and a model of efficient, passive dispersal.

Injecting Spores into Substrate: A Comprehensive Guide for Mushroom Growers

You may want to see also

Role of cones in gymnosperm spore dispersal strategies

Gymnosperms, unlike their angiosperm counterparts, rely on cones as the primary structures for spore production and dispersal. These cones are not merely protective casings but sophisticated mechanisms tailored to ensure the successful dissemination of spores. Cones come in two main types: male cones, which produce pollen (microspores), and female cones, which produce ovules (megaspores). The design and function of these cones are critical to the reproductive strategy of gymnosperms, enabling them to thrive in diverse environments, from dense forests to arid landscapes.

Consider the role of wind in spore dispersal, a strategy heavily dependent on cone structure. Male cones are typically smaller and produce lightweight pollen grains, which are easily carried by air currents. For instance, pine trees release vast quantities of pollen from their male cones, increasing the likelihood of reaching distant female cones. Female cones, on the other hand, are larger and more robust, often positioned higher on the tree to intercept wind-borne pollen. Once pollination occurs, the female cones mature, and their scales open to release seeds, which may also be wind-dispersed. This dual-cone system maximizes efficiency, ensuring that both spores and seeds are effectively distributed.

A closer examination of cone anatomy reveals adaptations that enhance dispersal. The scales of female cones, for example, often have winged structures or resinous coatings that aid in seed release and protection. In species like the Douglas fir, the cones dry out and open widely, allowing seeds to be ejected with force, a mechanism known as "ballistic dispersal." Similarly, some cones, such as those of the spruce, rely on gradual scale opening over time, ensuring a steady release of seeds rather than a single event. These variations highlight the evolutionary fine-tuning of cones to suit specific ecological niches.

Practical observations of cone behavior offer valuable insights for conservation and horticulture. For instance, gardeners cultivating gymnosperms like redwoods or cedars should mimic natural conditions by planting in open, windy areas to facilitate pollen flow. Additionally, understanding cone maturation cycles can guide seed collection efforts. For example, pine cones should be harvested when they begin to open naturally, typically in late summer or fall, to ensure maximum seed viability. By aligning human practices with the inherent strategies of cones, we can support the propagation and survival of these ancient plants.

In conclusion, cones are not passive players in gymnosperm reproduction but active agents in spore and seed dispersal. Their structural diversity and functional specificity underscore the adaptability of gymnosperms to their environments. Whether through wind-driven pollen release or strategic seed ejection, cones exemplify nature’s ingenuity in ensuring the continuity of life. By studying and respecting these mechanisms, we gain both scientific knowledge and practical tools for preserving these vital species.

Moss Spores and Allergies: Uncovering the Hidden Triggers in Your Environment

You may want to see also

Gravity's impact on gymnosperm spore distribution patterns

Gymnosperms, such as conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, rely on gravity as a primary mechanism for spore dispersal, particularly in the case of male gametophytes (pollen) and female ovules. Unlike angiosperms, which often employ wind, water, or animals for seed dispersal, gymnosperms frequently release their spores and pollen in a manner that allows gravity to dictate their initial distribution. This reliance on gravity is most evident in cone-bearing species, where pollen is shed from male cones and falls onto the scales of female cones below. The efficiency of this process is influenced by the height of the cones, the density of the pollen grains, and the environmental conditions that affect gravitational pull.

Consider the anatomical adaptations that facilitate gravity-driven dispersal. Male cones are typically positioned higher on the tree than female cones, ensuring that pollen falls downward under the influence of gravity. For example, in pine trees, male cones develop at the top of the branches, while female cones grow lower down. This vertical arrangement maximizes the likelihood of pollen reaching the receptive structures of the female cones. Additionally, the lightweight nature of pollen grains allows them to drift slightly in the air before settling, but gravity remains the dominant force guiding their descent. This process is highly localized, meaning that most pollination occurs within the same tree or nearby individuals, reducing the need for long-distance dispersal mechanisms.

While gravity is a reliable dispersal agent, it is not without limitations. The success of gravity-driven spore distribution depends on the proximity of male and female reproductive structures. In species where cones are widely spaced or trees are sparsely distributed, the effectiveness of this method diminishes. Environmental factors, such as strong winds or heavy rainfall, can also disrupt the gravitational descent of pollen, leading to reduced fertilization rates. To mitigate these challenges, some gymnosperms produce large quantities of pollen to increase the probability of successful dispersal. For instance, a single male cone of a pine tree can release millions of pollen grains, ensuring that even if a fraction reaches the female cones, pollination can still occur.

Practical observations of gravity’s role in gymnosperm spore distribution can be made by examining the spatial arrangement of cones on mature trees. During the pollination season, place a clean, white sheet or tray beneath a gymnosperm tree to collect falling pollen. Over time, you will notice a concentration of pollen directly below the male cones, demonstrating gravity’s influence. This simple experiment highlights the localized nature of gravity-driven dispersal and underscores the importance of tree structure in facilitating this process. For educators or enthusiasts, this activity provides a tangible way to study the reproductive biology of gymnosperms.

In conclusion, gravity plays a pivotal role in shaping the spore distribution patterns of gymnosperms, particularly through the vertical alignment of male and female cones and the production of lightweight pollen grains. While this method is efficient in ensuring localized pollination, it is constrained by the proximity of reproductive structures and susceptibility to environmental interference. Understanding these dynamics not only sheds light on the evolutionary adaptations of gymnosperms but also offers practical insights for conservation efforts and horticultural practices involving these ancient plants.

Exploring Moss Reproduction: Do Mosses Produce Two Distinct Types of Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Water-aided spore dispersal in aquatic gymnosperm species

Aquatic gymnosperms, though less common than their terrestrial counterparts, employ water as a primary agent for spore dispersal, leveraging the fluid medium to maximize reach and colonization potential. Unlike land-dwelling species that rely on wind or animals, these plants release spores directly into water currents, where they are carried to new habitats. For instance, *Cycas seychellensis*, an aquatic cycad endemic to the Seychelles, disperses its spores through river systems, ensuring genetic diversity across fragmented populations. This method is particularly effective in environments where wind dispersal is limited, such as dense tropical forests or submerged ecosystems.

To understand the mechanics of water-aided dispersal, consider the spore structure of aquatic gymnosperms. These spores are often larger and more robust than those of terrestrial species, enabling them to withstand the rigors of water transport. For example, the spores of *Ginkgo biloba* relatives found in fossil records suggest adaptations for buoyancy, such as air pockets or hydrophobic coatings. In practice, gardeners cultivating aquatic gymnosperms can mimic natural dispersal by introducing spores into slow-moving water bodies, ensuring they are evenly distributed to promote colonization. A dosage of 10–20 spores per liter of water is recommended for optimal dispersal without overcrowding.

A comparative analysis highlights the advantages of water dispersal over other methods. While wind dispersal is unpredictable and animal dispersal relies on external behavior, water provides a consistent and directional medium. However, this method is not without challenges. Spores must avoid predators and unfavorable conditions, such as rapid currents or pollutants, which can reduce viability. For conservationists, monitoring water quality and flow rates is crucial when reintroducing spores into wild habitats. Practical tips include using mesh filters to protect spores during transport and selecting release points upstream to maximize dispersal range.

Persuasively, water-aided dispersal offers a sustainable strategy for restoring aquatic gymnosperm populations, particularly in degraded ecosystems. By harnessing natural water currents, conservation efforts can achieve broader coverage with minimal intervention. For instance, in the restoration of *Zamites* species in wetland areas, spores released during the wet season have shown higher germination rates compared to manual planting. This approach not only reduces labor costs but also aligns with ecosystem-based management principles. Stakeholders should prioritize protecting waterways and maintaining hydrological connectivity to support long-term dispersal success.

In conclusion, water-aided spore dispersal in aquatic gymnosperms is a specialized adaptation that combines efficiency with ecological harmony. From the structural resilience of spores to the strategic use of water currents, this mechanism exemplifies nature’s ingenuity. Whether for conservation, cultivation, or research, understanding and replicating these processes can ensure the survival and proliferation of these unique plants. By focusing on water quality, spore dosage, and environmental conditions, practitioners can optimize dispersal outcomes and contribute to the preservation of aquatic gymnosperm biodiversity.

Inoculated Spores Moldy? Troubleshooting Contamination in Your Fermentation Project

You may want to see also

Animal-assisted spore dispersal in gymnosperm ecosystems

Gymnosperms, such as conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, rely on wind pollination for reproduction, but their spore dispersal mechanisms are less understood. While wind plays a significant role in dispersing pollen, animal-assisted spore dispersal is a fascinating, underappreciated process in gymnosperm ecosystems. This symbiotic relationship not only aids in the survival of these ancient plants but also highlights the intricate connections within their habitats.

Consider the role of birds and small mammals in cycad ecosystems. Cycads produce large, fleshy seeds that are toxic to many organisms due to the presence of cycasin. However, certain birds, like the New Caledonian crow, and mammals, such as agoutis, have evolved resistance to these toxins. These animals consume the seeds, digest the outer layer, and disperse the inner seed intact through their feces. This process, known as zoochory, ensures seeds are deposited in nutrient-rich areas, increasing germination success. For instance, agoutis in South America bury cycad seeds for later consumption, inadvertently acting as seed dispersers when they forget some caches.

In conifer forests, rodents like squirrels and chipmunks contribute to spore and seed dispersal indirectly. While gymnosperms primarily produce pollen and seeds, these animals gather and store cones for food. As they transport cones to their nests or caches, pollen and seeds may be inadvertently released, facilitating dispersal. A study in the Pacific Northwest found that Douglas squirrels disperse up to 20% of the cones they collect, significantly aiding forest regeneration. To encourage this behavior, landowners can maintain diverse understory vegetation, providing habitat for these rodents.

Persuasively, integrating animal-assisted dispersal into conservation strategies is crucial for gymnosperm survival. For example, protecting bird and mammal populations in cycad habitats ensures continued seed dispersal, particularly for endangered species like the Coontie palm. Similarly, preserving old-growth conifer forests supports rodent populations, which are essential for natural regeneration. Conservationists should prioritize habitat connectivity, allowing animals to move freely and disperse spores across fragmented landscapes.

Descriptively, the relationship between gymnosperms and animals is a delicate dance of mutual benefit. Birds like the Mariana fruit dove in Guam consume cycad seeds, while their droppings provide nutrients to the soil, fostering healthier plant growth. In return, the cycads offer a reliable food source during seasons when other resources are scarce. This interdependence underscores the importance of preserving biodiversity in gymnosperm ecosystems, as the loss of one species can disrupt the entire reproductive cycle.

In conclusion, animal-assisted spore dispersal in gymnosperm ecosystems is a vital yet often overlooked process. From cycads relying on toxin-resistant animals to conifers benefiting from rodent caching behaviors, these relationships demonstrate nature’s ingenuity. By understanding and protecting these interactions, we can ensure the longevity of gymnosperms and the ecosystems they support. Practical steps include habitat restoration, species reintroduction, and public education to highlight the role of animals in plant reproduction.

Do Stoneworts Produce Spores? Unveiling Their Unique Reproductive Secrets

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Gymnosperms disperse their spores primarily through wind. Male cones produce microspores that are lightweight and easily carried by air currents to reach female cones for fertilization.

Yes, gymnosperms produce both microspores (male) and megaspores (female). Microspores develop into pollen grains, while megaspores remain within the ovule for fertilization.

While wind is the primary method, some gymnosperms rely on animals or water for secondary dispersal of seeds after fertilization, though spores themselves are mainly wind-dispersed.

Gymnosperm spores are dispersed directly from cones via wind, whereas angiosperms typically rely on flowers and fruits for seed dispersal, often involving animals, water, or explosive mechanisms.