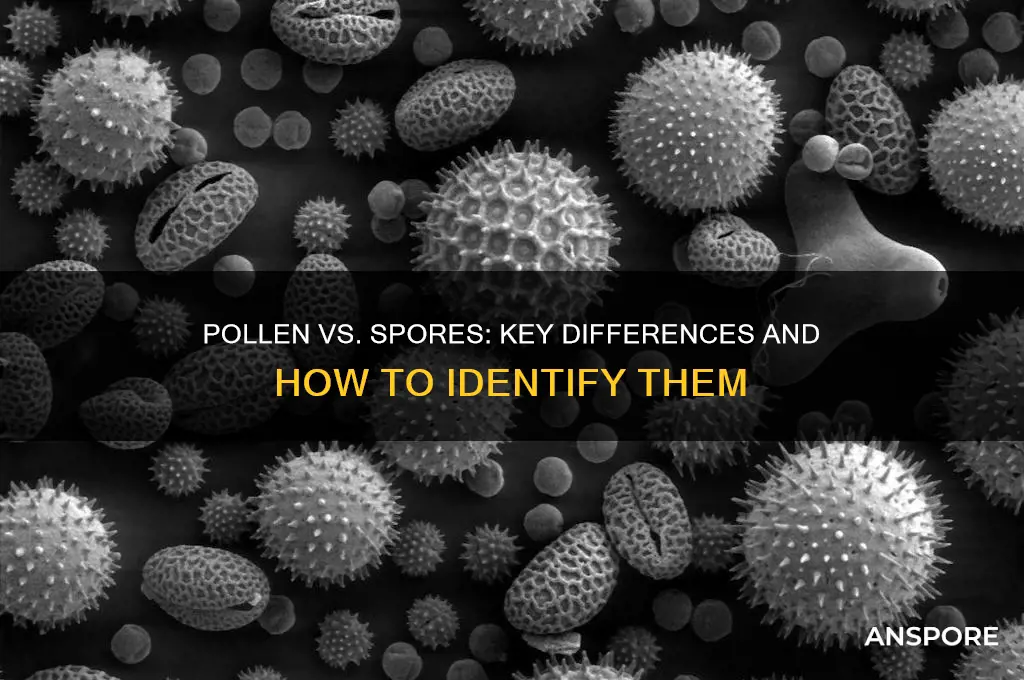

Distinguishing between pollen and spores is essential in botany and microbiology, as both are microscopic reproductive structures but serve different functions. Pollen, produced by seed plants like flowering plants and conifers, is a male gametophyte involved in fertilization, typically characterized by its grain-like structure, often with distinct shapes and surface textures optimized for wind or animal dispersal. Spores, on the other hand, are produced by non-seed plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) and fungi, serving as asexual reproductive units or for dispersal in adverse conditions. They are generally smaller, simpler in structure, and lack the specialized features of pollen. Microscopic examination, including size, shape, and surface details, along with knowledge of the parent organism, is crucial for accurate identification.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Size | Pollen grains are generally larger (20-80 μm) than spores (10-50 μm). |

| Shape | Pollen often has distinctive shapes (e.g., spherical, oval, or complex) with surface sculpturing (e.g., spines, ridges), while spores are typically more uniform and simpler in shape (e.g., round, oval, or kidney-shaped). |

| Wall Structure | Pollen has a complex, multi-layered wall (exine and intine) with intricate patterns, whereas spores have a simpler, single-layered wall (sporopollenin) that is thicker and more resistant to degradation. |

| Function | Pollen is the male gametophyte in seed plants, involved in fertilization, while spores are reproductive units in plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) and fungi, capable of developing into new individuals. |

| Production | Pollen is produced in the anthers of flowers (angiosperms) or cones (gymnosperms), whereas spores are produced in sporangia (plants) or sporocarps (fungi). |

| Dispersal | Pollen is often wind or insect-dispersed, while spores are typically wind-dispersed or released in water. |

| Germination | Pollen germinates to form a pollen tube for fertilization, whereas spores germinate to produce a gametophyte or new organism. |

| Allergenicity | Pollen is a common allergen in humans, causing hay fever, while spores are less frequently allergenic but can cause respiratory issues in sensitive individuals. |

| Fossil Record | Pollen fossils are used in palynology to study past plant communities, while spore fossils provide insights into ancient fungi and early land plants. |

| Taxonomic Significance | Pollen morphology is crucial for identifying plant species, whereas spore characteristics are key to classifying fungi and lower plants. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Size and Shape Differences: Pollen grains are larger, often symmetrical, while spores are smaller, simpler in structure

- Surface Texture: Pollen has intricate patterns (e.g., spines, ridges), spores are smoother or lightly ornamented

- Function and Origin: Pollen aids reproduction in seed plants; spores are for fungi, ferns, and mosses

- Cell Structure: Pollen is multicellular with a tube cell; spores are typically single-celled or simple

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Pollen relies on wind, insects; spores use wind, water, or animals for spread

Size and Shape Differences: Pollen grains are larger, often symmetrical, while spores are smaller, simpler in structure

Pollen grains and spores, though both microscopic, exhibit distinct size and shape characteristics that can aid in their identification. A key differentiator lies in their dimensions: pollen grains typically measure between 10 to 100 micrometers in diameter, making them visible under a low-power microscope. Spores, on the other hand, are generally smaller, ranging from 2 to 50 micrometers. This size disparity is not arbitrary; it reflects their respective functions. Pollen, designed for fertilization, often requires larger structures to carry genetic material and nutrients. Spores, being agents of asexual reproduction and dispersal, prioritize lightweight, compact forms for efficient travel.

Consider the shapes of these microscopic entities. Pollen grains frequently display intricate, symmetrical designs—think of the tri-lobed structure of oak pollen or the spiky, sunburst-like appearance of sunflower pollen. These complex shapes often serve to enhance adhesion to pollinators or facilitate germination. Spores, in contrast, tend toward simpler, more uniform shapes, such as spheres or ellipsoids. For instance, fern spores are typically smooth and round, optimized for wind dispersal. This simplicity in spore structure underscores their primary role: survival and propagation in diverse environments.

To illustrate, imagine examining samples under a microscope. A slide of pine pollen reveals grains with distinct air sacs and a symmetrical, granular surface, measuring around 50 micrometers. Nearby, a slide of mold spores shows tiny, oval structures, barely 10 micrometers across, with no visible ornamentation. This visual comparison highlights the size and shape differences, making it easier to distinguish between the two. For enthusiasts or students, practicing with common samples like ragweed pollen (20–30 micrometers, spiky) and moss spores (10–20 micrometers, smooth) can sharpen observational skills.

Practical tips for identification include using a 40x objective lens for initial observation, as this magnification level provides a clear view of size and shape without overwhelming detail. Measurements can be approximated using a micrometer slide for calibration. For advanced analysis, software tools like ImageJ allow precise sizing and shape analysis, though this may be overkill for casual observers. A simple rule of thumb: if the structure appears intricate and larger than 20 micrometers, it’s likely pollen; if small, smooth, and under 20 micrometers, it’s probably a spore.

In conclusion, size and shape offer a straightforward yet powerful method for differentiating pollen grains from spores. By focusing on these characteristics, even novice observers can quickly gain confidence in their identifications. Whether for academic study, allergy monitoring, or botanical curiosity, mastering this distinction opens a window into the microscopic world of plant reproduction and survival.

Are Botulism Spores Airborne? Unraveling the Truth and Risks

You may want to see also

Surface Texture: Pollen has intricate patterns (e.g., spines, ridges), spores are smoother or lightly ornamented

Under a microscope, the surface of a pollen grain often resembles a tiny, intricate fortress. Its walls are fortified with spines, ridges, or intricate mesh-like patterns, each designed to aid in dispersal and adhesion. These features are not merely decorative; they serve functional roles, such as hooking onto animal fur or withstanding harsh environmental conditions. For instance, pine pollen grains exhibit pronounced air sacs and spines, optimizing wind dispersal. In contrast, spores—the reproductive units of fungi, ferns, and mosses—present a smoother, almost minimalist surface. While some spores may have subtle ridges or warts, their texture lacks the complexity of pollen. This difference in surface ornamentation is a key diagnostic feature for distinguishing between the two under magnification.

To identify pollen and spores based on surface texture, start by examining the specimen at 400x to 1000x magnification. Look for the presence of spines, ridges, or reticulated patterns, which strongly indicate pollen. For example, ragweed pollen has distinct spines, while sunflower pollen displays a netted pattern. Spores, on the other hand, will appear smoother or lightly ornamented, often with a uniform texture. A practical tip: use a micrometer slide to measure the size of the particle, as pollen grains typically range from 10 to 100 micrometers, while spores are generally smaller, often under 50 micrometers. This combination of texture and size analysis can provide a quick, reliable distinction.

The evolutionary rationale behind these textural differences is fascinating. Pollen’s intricate surface is adapted for survival in diverse environments, from wind-pollinated plants with smooth but textured grains to insect-pollinated species with sticky or barbed surfaces. Spores, however, prioritize lightweight efficiency for long-distance dispersal, often relying on smoothness to reduce drag. For educators or hobbyists, demonstrating this contrast using common samples—such as lily pollen (with its reticulated surface) versus fern spores (nearly smooth)—can make the lesson tangible. Always handle specimens carefully, using clean slides and coverslips to avoid contamination that could obscure surface details.

While surface texture is a powerful identifier, it’s not foolproof. Some spores, like those of certain fungi, may exhibit fine ornamentation that mimics pollen. In such cases, cross-reference with other characteristics, such as shape or wall structure. For advanced users, staining techniques (e.g., safranin or cotton blue) can enhance surface details, though this is optional for basic identification. Remember, the goal is to observe, compare, and deduce—a process that sharpens both observational skills and appreciation for the microscopic world’s diversity.

Breathing Fungal Spores: Uncovering Potential Health Risks and Concerns

You may want to see also

Function and Origin: Pollen aids reproduction in seed plants; spores are for fungi, ferns, and mosses

Pollen and spores, though microscopic, play vastly different roles in the natural world. Pollen is the male reproductive agent of seed plants, including flowering plants (angiosperms) and cone-bearing plants (gymnosperms). Each pollen grain contains the genetic material necessary to fertilize the female ovule, leading to seed formation. In contrast, spores are the reproductive units of non-seed plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. These single-celled structures are designed for dispersal and can develop into new organisms under favorable conditions. Understanding this fundamental difference in function is key to distinguishing between the two.

To identify pollen, consider its origin and purpose. Pollen grains are typically produced in the anthers of flowers or the cones of gymnosperms. They are often brightly colored, ranging from yellow to orange, and are sticky or spiny to facilitate attachment to pollinators like bees or wind currents. Under a microscope, pollen grains exhibit a hard outer layer called the exine, which protects the genetic material inside. For example, pine pollen is large and winged, adapted for wind dispersal, while sunflower pollen is smaller and smooth, suited for insect transport. Practical tip: If you’re examining a flowering plant and notice tiny, colorful grains on the stigma or in the air, you’re likely observing pollen.

Spores, on the other hand, are the product of fungi, ferns, and mosses, organisms that lack seeds and flowers. Fungal spores are often single-celled and produced in vast quantities to ensure widespread dispersal. Fern spores are found on the undersides of fronds in structures called sori, appearing as small, dot-like clusters. Moss spores are housed in capsules atop slender stalks. Unlike pollen, spores are not involved in fertilization but instead grow directly into new individuals, often through a gametophyte stage. For instance, a single fern spore can develop into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte that eventually produces the next generation of ferns.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrasting strategies of pollen and spores. Pollen is specialized for targeted reproduction, relying on pollinators or wind to reach a specific destination—the female reproductive structure. Spores, however, are generalists, dispersed en masse to colonize new environments. Pollen’s protective exine ensures survival during transport, while spores often have thick walls to withstand harsh conditions. This divergence reflects the evolutionary adaptations of seed plants versus non-seed plants and fungi.

In practical terms, distinguishing between pollen and spores can be crucial for fields like botany, ecology, and allergy management. For example, pollen counts are monitored to predict allergy seasons, while spore identification helps in understanding fungal or fern populations. To tell them apart, examine their source: if it’s a flowering or cone-bearing plant, you’re dealing with pollen; if it’s a fern, moss, or fungus, it’s spores. Microscopic observation of shape, size, and surface features further confirms their identity. By understanding their function and origin, you can accurately differentiate these microscopic powerhouses of the plant and fungal kingdoms.

Mastering Spore Prints: A Simple Guide to Capturing Mushroom Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cell Structure: Pollen is multicellular with a tube cell; spores are typically single-celled or simple

Pollen and spores, though both reproductive units in plants, differ fundamentally in their cellular structure. Pollen grains are multicellular, typically consisting of two or three cells at maturity. One of these cells is the tube cell, also known as the vegetative cell, which plays a critical role in fertilization by growing a pollen tube to deliver sperm cells to the ovule. This complexity reflects pollen’s specialized function in angiosperms and some gymnosperms. In contrast, spores are generally single-celled or structurally simple, designed for dispersal and survival rather than immediate fertilization. This distinction in cell structure is a key morphological feature for distinguishing between the two.

To identify pollen under a microscope, look for the presence of a tube cell, which is often larger and more prominent than the other cells. In mature pollen grains of flowering plants, the tube cell is usually visible as a distinct structure, while the generative cell (containing the sperm nuclei) is smaller and embedded within it. Spores, on the other hand, lack this multicellular organization. For example, fern spores are single-celled and uniform in appearance, with no specialized structures for fertilization. This simplicity aligns with their role in asexual reproduction and long-distance dispersal.

Practical tip: When examining samples, use a staining technique like basic fuchsin or calcofluor white to highlight cell walls and internal structures. Pollen grains will show a clear division between the tube cell and other components, while spores will appear as uniform, undivided units. For beginners, start with easily accessible samples like pine pollen (multicellular) and fern spores (single-celled) to practice identifying these differences.

The evolutionary implications of these structural differences are significant. Pollen’s multicellular nature, particularly the presence of a tube cell, reflects the advanced reproductive strategy of seed plants, which ensures direct delivery of sperm to the egg. Spores, with their simplicity, are more primitive and versatile, allowing plants like ferns and mosses to thrive in diverse environments through asexual reproduction. Understanding these structural adaptations provides insight into the evolutionary divergence of plant reproductive systems.

In summary, the cellular structure of pollen and spores offers a clear diagnostic feature for differentiation. Pollen’s multicellularity, including its specialized tube cell, contrasts sharply with the single-celled or simple nature of spores. By focusing on these structural details, even non-specialists can accurately distinguish between the two, enhancing their understanding of plant biology and reproductive strategies.

Do Diploid Cells Undergo Meiosis to Form Spores? Exploring the Process

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Pollen relies on wind, insects; spores use wind, water, or animals for spread

Pollen and spores, though both reproductive units, employ distinct strategies for dispersal, reflecting their evolutionary adaptations to different environments and reproductive needs. Pollen, primarily produced by seed plants like angiosperms and gymnosperms, relies heavily on wind and insects for dissemination. Wind-pollinated plants, such as grasses and many trees, produce lightweight, smooth pollen grains in large quantities to increase the likelihood of reaching a receptive stigma. Insect-pollinated plants, on the other hand, invest in sticky, protein-rich pollen grains that adhere to pollinators like bees, butterflies, and beetles. These grains are often larger and more nutrient-dense, serving as a food reward for the insects that facilitate their transport.

Spores, produced by non-seed plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, exhibit a broader range of dispersal mechanisms. While wind remains a common method, spores are also adapted for water and animal-mediated spread. For instance, fungal spores often have hydrophobic surfaces that allow them to float on water, ensuring they can travel through aquatic environments. Some spores, like those of certain ferns, are equipped with structures such as elaters that help them disperse in response to changes in humidity. Animal dispersal is less common but occurs in species like the bird’s nest fungus, whose spore-containing structures are ingested and spread by animals. This diversity in dispersal methods underscores the versatility of spores in colonizing varied habitats.

To distinguish pollen from spores based on their dispersal mechanisms, consider the following practical tips. Examine the plant or organism in question: if it is a flowering plant, the reproductive units are likely pollen, dispersed by wind or insects. If it is a fern, moss, or fungus, the units are spores, which may rely on wind, water, or animals. Observe the environment—wind-dispersed units are often found in open, airy spaces, while water-dispersed spores are more common in damp or aquatic areas. For a hands-on approach, collect samples and examine them under a microscope: pollen grains typically have a more complex, sculptured surface, while spores are often smoother and more uniform.

The ecological implications of these dispersal mechanisms are profound. Pollen’s reliance on wind and insects ties it closely to specific habitats and seasons, influencing plant distribution and genetic diversity. Spores’ adaptability to multiple dispersal methods allows them to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from arid deserts to dense forests. Understanding these differences not only aids in identification but also highlights the intricate ways in which plants and fungi have evolved to ensure their survival and propagation. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into the delicate balance of nature and the strategies organisms employ to persist in a changing world.

Protozoan Cysts vs. Spores: Unraveling Their Striking Similarities and Differences

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Pollen is produced by seed-bearing plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) for reproduction, while spores are produced by non-seed plants (like ferns, mosses, and fungi) and some algae for asexual reproduction or dispersal.

Pollen grains often have distinct shapes, sizes, and surface structures (e.g., spines, ridges) adapted for wind or animal dispersal. Spores are typically smaller, smoother, and more uniform in shape, as they are designed for survival and dispersal rather than fertilization.

Yes, pollen is involved in sexual reproduction, carrying male gametes to fertilize female ovules. Spores, on the other hand, are used for asexual reproduction, dispersal, or survival in harsh conditions, and can develop into new organisms without fertilization.

No, pollen is produced by flowering plants (angiosperms) and conifers (gymnosperms), while spores are produced by non-flowering plants (like ferns, mosses, and liverworts) and fungi.

Yes, both can cause allergies, but pollen allergies (hay fever) are more common and typically seasonal, triggered by wind-borne pollen from grasses, trees, and weeds. Spores, particularly mold spores, can cause year-round allergies and are often associated with damp environments.