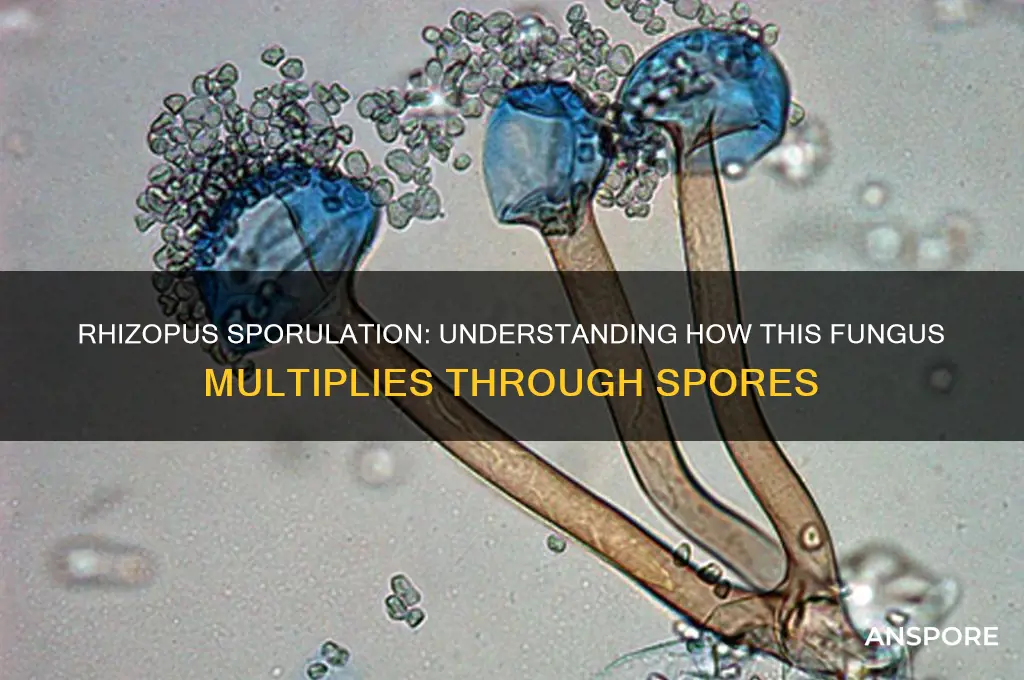

Rhizopus, a common mold belonging to the Zygomycota phylum, primarily multiplies through the production and dispersal of spores. This asexual reproductive process begins with the development of sporangia, which are spherical structures located at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. Within each sporangium, numerous haploid spores, known as sporangiospores, are formed through mitosis. Once mature, the sporangium wall ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. These lightweight spores are easily dispersed by air currents, allowing Rhizopus to colonize new substrates. Upon landing in a suitable environment with adequate moisture and nutrients, the spores germinate, producing new hyphae that grow and develop into a new mycelium, thus completing the life cycle. This efficient method of spore-mediated reproduction enables Rhizopus to rapidly spread and thrive in diverse habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Spores | Rhizopus primarily multiplies through asexual spores called sporangiospores. |

| Sporangium Formation | Spores are produced within a spherical structure called a sporangium, which develops at the tip of a specialized hyphal branch (sporangiophore). |

| Sporangiophore Growth | Sporangiophores grow rapidly and are often erect, bearing a single sporangium at the apex. |

| Sporangium Maturation | As the sporangium matures, it fills with haploid spores through mitotic divisions of the sporangial cells. |

| Sporangium Color | Mature sporangia are typically black or dark gray due to the accumulation of spores. |

| Sporangium Rupture | Upon maturity, the sporangium wall ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are dispersed by air currents, water, or physical contact, allowing Rhizopus to colonize new substrates. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions, producing a germ tube that develops into new hyphae. |

| Environmental Requirements | Sporulation and germination require warmth, moisture, and a suitable organic substrate. |

| Role in Life Cycle | This asexual reproduction method allows Rhizopus to rapidly propagate and survive in diverse environments. |

Explore related products

$9.95 $11.99

What You'll Learn

- Sporangia Formation: Rhizopus develops sporangia, sac-like structures containing spores, at the tips of sporangiophores

- Spores Release: Sporangia mature, dry, and rupture, releasing numerous spores into the environment

- Environmental Factors: High humidity and warm temperatures trigger spore production and dispersal

- Germination Process: Spores land on suitable substrates, absorb water, and germinate to form new hyphae

- Asexual Reproduction: Spores are the primary means of asexual reproduction, ensuring rapid colonization

Sporangia Formation: Rhizopus develops sporangia, sac-like structures containing spores, at the tips of sporangiophores

Rhizopus, a common mold found on decaying organic matter, employs a fascinating reproductive strategy centered on sporangia formation. These sac-like structures, brimming with spores, are the key to its prolific multiplication. The process begins with the development of sporangiophores, slender, stalk-like projections that emerge from the fungus's mycelium. At the apex of each sporangiophore, a sporangium forms, serving as a protective chamber for the spores within. This strategic placement ensures optimal dispersal, as the elevated position facilitates the release of spores into the surrounding environment.

The formation of sporangia is a highly coordinated process, regulated by environmental cues such as nutrient availability and humidity. When conditions are favorable, Rhizopus accelerates sporangium development, producing thousands of spores within a short period. Each sporangium can contain anywhere from 5,000 to 50,000 spores, depending on species and environmental factors. These spores are not only numerous but also remarkably resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions such as desiccation and extreme temperatures. This adaptability ensures the fungus's survival and proliferation across diverse ecosystems.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporangia formation is crucial for controlling Rhizopus growth, particularly in agricultural and food storage settings. For instance, maintaining low humidity levels (below 60%) can inhibit sporangium development, as the fungus thrives in moist environments. Additionally, regular inspection of susceptible materials, such as bread or fruits, can help detect early signs of mold growth. If sporangiophores are observed, immediate removal and disposal of the contaminated item can prevent spore dispersal. For larger-scale applications, fungicides containing active ingredients like potassium sorbate or natamycin can be applied at recommended dosages (typically 0.1–0.5% concentration) to suppress mold growth.

Comparatively, the sporangia of Rhizopus differ from those of other fungi in their rapid maturation and explosive release mechanism. Unlike the more gradual spore release seen in species like *Aspergillus*, Rhizopus sporangia rupture suddenly, ejecting spores into the air with considerable force. This explosive dispersal is aided by the sporangium's thin, delicate walls, which dry out and split under tension. The efficiency of this mechanism highlights Rhizopus's evolutionary specialization for quick colonization of new substrates.

In conclusion, sporangia formation in Rhizopus is a remarkable example of fungal adaptation, combining structural precision with environmental responsiveness. By focusing on the unique features of sporangiophores and sporangia, one gains insight into both the fungus's life cycle and effective strategies for its management. Whether in a laboratory, kitchen, or industrial setting, recognizing the signs of sporangia development is the first step toward mitigating Rhizopus's impact and harnessing its ecological role.

How Mold Spores Invisibly Spread and Contaminate Everything Around Us

You may want to see also

Spores Release: Sporangia mature, dry, and rupture, releasing numerous spores into the environment

The maturation of sporangia in *Rhizopus* marks a critical phase in its reproductive cycle. As these structures mature, they undergo a transformation from plump, moisture-rich sacs to dry, brittle capsules. This desiccation is not a sign of decay but a strategic preparation for spore release. The drying process weakens the sporangial walls, setting the stage for the next step: rupture. When conditions are optimal—typically in dry, warm environments—the sporangia crack open, dispersing their contents with remarkable efficiency. This mechanism ensures that spores are released en masse, maximizing the fungus’s chances of colonizing new substrates.

Consider the analogy of a ripe fruit bursting at its seams. Just as a fruit releases seeds to propagate its species, *Rhizopus* sporangia rupture to scatter spores far and wide. However, unlike seeds, which rely on external agents like wind or animals, *Rhizopus* spores are lightweight and aerodynamic, designed for passive dispersal. This adaptation allows them to travel significant distances, even in still air. For instance, a single sporangium can release up to 50,000 spores, each capable of germinating under favorable conditions. This sheer volume increases the likelihood of successful colonization, a key survival strategy for this saprophytic fungus.

Practical observation of this process can be achieved with simple laboratory techniques. Place a mature *Rhizopus* colony on a bread slice or agar plate and observe it over 48–72 hours. As sporangia mature, their color shifts from opaque to a darker hue, signaling readiness. Gently tapping the substrate or exposing it to a mild air current can simulate natural conditions, triggering spore release. For educational purposes, a magnifying glass or low-power microscope can reveal the cloud of spores dispersing, offering a tangible demonstration of this reproductive mechanism.

While the release of spores is a natural and efficient process, it poses challenges in controlled environments. In food storage, for example, *Rhizopus* spores can contaminate bread, fruits, or vegetables, leading to rapid spoilage. To mitigate this, maintain humidity below 60% and temperatures under 20°C, as these conditions inhibit sporangial maturation. Additionally, regular inspection of stored produce can help identify early signs of fungal growth, allowing for timely removal of infected items. Understanding the spore release mechanism empowers both scientists and everyday individuals to manage *Rhizopus* proliferation effectively.

In conclusion, the rupture of mature, dry sporangia is a finely tuned process that exemplifies *Rhizopus*’s adaptability and resilience. By releasing spores in vast quantities, this fungus ensures its survival across diverse environments. Whether observed in a lab or encountered in daily life, this reproductive strategy underscores the importance of environmental control in managing fungal growth. From educational insights to practical applications, the spore release phase of *Rhizopus* offers a fascinating glimpse into the intricacies of microbial life.

Mold Spores and Chronic Migraines: Uncovering the Long-Term Connection

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors: High humidity and warm temperatures trigger spore production and dispersal

Rhizopus, a common mold found in various environments, thrives under specific conditions that catalyze its reproductive cycle. High humidity and warm temperatures act as the primary triggers for spore production and dispersal, making these factors critical to understanding its proliferation. When relative humidity exceeds 80% and temperatures range between 25°C to 30°C (77°F to 86°F), Rhizopus enters an optimal state for sporulation. These conditions mimic its natural habitats, such as decaying organic matter or damp indoor spaces, where it can rapidly multiply.

Analyzing the mechanism reveals a survival strategy honed by evolution. Warmth accelerates metabolic processes within the fungus, enabling faster growth and energy allocation to spore development. Simultaneously, high humidity ensures the spores remain viable and easily dispersible, as dry conditions could render them dormant or brittle. This synergy between temperature and moisture creates an ideal environment for Rhizopus to colonize new areas. For instance, in food storage facilities with poor ventilation, these conditions can lead to widespread contamination within days.

To mitigate Rhizopus proliferation, controlling environmental factors is key. Reducing indoor humidity below 60% using dehumidifiers or proper ventilation disrupts spore production. Maintaining temperatures below 20°C (68°F) in storage areas can further inhibit growth. For agricultural settings, ensuring crops are dried thoroughly before storage prevents the damp conditions Rhizopus requires. These practical steps, grounded in understanding its environmental triggers, can significantly reduce the risk of infestation.

Comparatively, other fungi may have different thresholds for sporulation, but Rhizopus stands out for its rapid response to warmth and moisture. Unlike Penicillium, which prefers cooler temperatures, Rhizopus is uniquely adapted to tropical and subtropical climates. This distinction highlights the importance of tailored environmental management strategies. By focusing on humidity and temperature, one can effectively target Rhizopus while leaving beneficial microorganisms less affected.

In conclusion, high humidity and warm temperatures are not mere coincidental factors but essential catalysts for Rhizopus spore production and dispersal. Recognizing this relationship empowers individuals and industries to implement precise preventive measures. Whether in homes, farms, or factories, controlling these environmental variables is a proactive defense against Rhizopus proliferation, ensuring healthier spaces and preserved resources.

Can Green Moss Plants Sprout from Spores? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Process: Spores land on suitable substrates, absorb water, and germinate to form new hyphae

Spores of *Rhizopus*, the fungus behind common molds like black bread mold, are microscopic survival units designed for dispersal and persistence. When a spore lands on a suitable substrate—think damp bread, decaying fruit, or nutrient-rich soil—it initiates a precise sequence of events to ensure the fungus’s proliferation. The first critical step is water absorption, a process called imbibition. Without sufficient moisture, the spore remains dormant, a hardened shell impervious to environmental cues. Once water is available, the spore swells, reactivating its metabolic processes and setting the stage for germination.

The germination process is both rapid and resource-efficient, a testament to *Rhizopus*’s adaptability. Within hours of water absorption, the spore’s internal enzymes begin breaking down stored nutrients, fueling the emergence of a germ tube. This tube, the precursor to new hyphae, grows toward the substrate’s surface, guided by chemical signals and nutrient gradients. The substrate itself plays a dual role: it provides physical support and acts as a nutrient reservoir, ensuring the developing hyphae have immediate access to carbohydrates, proteins, and other essential compounds. For optimal germination, substrates with a water activity (aw) of 0.90–0.99 are ideal, as lower moisture levels inhibit growth, while higher levels risk drowning the spore.

Practical observation reveals the germination process’s sensitivity to environmental conditions. For instance, spores on bread at room temperature (25°C) germinate within 6–12 hours, while those on cooler surfaces (15°C) may take up to 24 hours. Humidity is equally critical; spores exposed to relative humidity below 80% often fail to imbibe water, remaining dormant. To encourage germination in laboratory settings, researchers often pre-treat spores with a 0.1% Tween 80 solution, which reduces surface tension and enhances water uptake. Home gardeners combating *Rhizopus* on plants can exploit this sensitivity by reducing humidity and improving air circulation, effectively disrupting the germination process.

Comparatively, *Rhizopus*’s germination efficiency outpaces many other fungi, a trait linked to its asexual reproductive strategy. Unlike basidiomycetes, which rely on complex mating systems, *Rhizopus* produces spores (sporangiospores) in vast quantities, ensuring at least some land on favorable substrates. This high-volume approach, combined with rapid germination, allows *Rhizopus* to colonize resources quickly, outcompeting slower-growing organisms. However, this efficiency comes with a trade-off: the hyphae are more susceptible to desiccation once established, underscoring the spore’s role as the primary survival and dispersal unit.

In conclusion, the germination of *Rhizopus* spores is a finely tuned process, balancing speed, efficiency, and environmental responsiveness. From the initial absorption of water to the emergence of new hyphae, each step is optimized for survival and proliferation. Understanding this process not only sheds light on *Rhizopus*’s ecological success but also offers practical strategies for managing its growth, whether in food preservation, agriculture, or laboratory research. By manipulating moisture, temperature, and substrate composition, one can either foster or inhibit this remarkable fungal lifecycle.

Mold Spores and Breathing: Uncovering Their Impact on Respiratory Health

You may want to see also

Asexual Reproduction: Spores are the primary means of asexual reproduction, ensuring rapid colonization

Spores are the silent architects of *Rhizopus*’s dominion, enabling this fungus to colonize environments with astonishing speed. Unlike sexual reproduction, which requires a partner and favorable conditions, asexual reproduction through spores is a solo act of efficiency. *Rhizopus* produces sporangiospores within sac-like structures called sporangia, which, when mature, burst open to release thousands of spores into the air or surrounding medium. This method ensures that even a single individual can rapidly propagate, making it ideal for unpredictable environments where resources are fleeting.

Consider the mechanics of spore dispersal: lightweight and often equipped with structures like elaters (coiled appendages that aid in ejection), these spores travel far and wide on air currents or via water. Once they land in a suitable environment—moist, nutrient-rich substrates like decaying fruit or soil—they germinate within hours. This rapid colonization strategy is critical for *Rhizopus*, as it competes with other microorganisms for resources. For instance, in a rotting apple, *Rhizopus* spores can outpace bacteria and other fungi by quickly establishing a foothold and absorbing nutrients before others can dominate.

The efficiency of spore-based reproduction lies in its simplicity and scalability. Each spore is a self-contained unit of life, capable of developing into a new mycelium without the need for genetic recombination. This uniformity ensures consistency in traits like nutrient absorption and growth rate, which are vital for survival in stable environments. However, it’s worth noting that while asexual reproduction is fast, it lacks the genetic diversity introduced by sexual reproduction. Over time, this can limit adaptability to new challenges like antifungal agents or climate shifts.

Practical implications of *Rhizopus*’s spore-driven colonization are evident in food spoilage and industrial applications. In food storage, controlling humidity and temperature is key to preventing spore germination, as *Rhizopus* thrives in warm, damp conditions. Conversely, in biotechnology, its rapid growth via spores is harnessed for producing enzymes and organic acids. For example, *Rhizopus* is used in the fermentation of tempeh, where its mycelium binds soybeans into a nutritious cake. Here, understanding spore behavior allows for optimized conditions to maximize yield while minimizing contamination.

In essence, spores are *Rhizopus*’s secret weapon for survival and expansion. Their production and dispersal exemplify nature’s ingenuity in solving the challenge of rapid proliferation. Whether viewed as a nuisance in food preservation or a tool in biotechnology, mastering the dynamics of spore-based asexual reproduction offers insights into both controlling and leveraging this remarkable organism.

Unveiling the Flood Spore Infection: Truth's Contamination Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Rhizopus multiplies by producing spores, specifically asexual spores called sporangiospores, which are formed inside a structure called a sporangium.

Rhizopus produces asexual spores called sporangiospores, which are released from the sporangium and disperse to initiate new growth.

The spores of Rhizopus are formed inside a spherical structure called a sporangium, which develops at the tip of a specialized hyphal structure known as a sporangiophore.

Rhizopus spores are dispersed through air currents, water, or physical contact once the sporangium ruptures or dries out, releasing the spores into the environment.

Yes, under certain conditions, Rhizopus can produce sexual spores called zygospores through the fusion of compatible hyphae, resulting in a thick-walled zygospore that can survive harsh conditions.