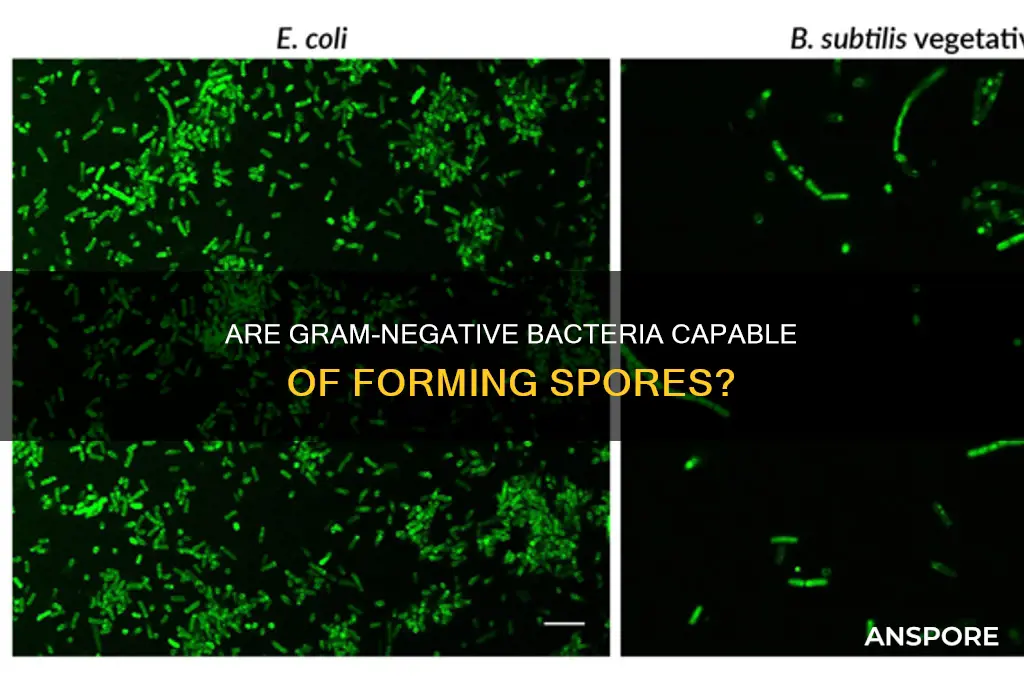

The question of whether a Gram-negative cell is a spore is a common point of confusion in microbiology. Gram-negative bacteria are characterized by their thin peptidoglycan cell wall and outer membrane, which distinguishes them from Gram-positive bacteria. Spores, on the other hand, are highly resistant, dormant structures produced by certain bacteria, primarily Gram-positive species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, as a survival mechanism in harsh conditions. While Gram-negative bacteria do not typically form spores, some exceptions exist, such as *Bacillus* species that are Gram-variable or *Clostridium* species that may exhibit Gram-negative staining under certain conditions. However, the majority of Gram-negative bacteria rely on other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation or persistence, to survive adverse environments, making spore formation a rare trait in this group.

What You'll Learn

Spore Formation in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are primarily known for their distinctive cell wall structure, which includes an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides. Unlike their gram-positive counterparts, they generally do not form spores as a survival mechanism. However, there are exceptions to this rule, and understanding these rare instances is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications in fields like medicine and biotechnology.

One notable example of spore formation in gram-negative bacteria is observed in the genus *Bacillus*, though it is important to clarify that *Bacillus* species are actually gram-positive. This highlights the rarity of spore formation in gram-negative bacteria. Among gram-negative bacteria, *Adenylosuccinate synthetase* (AdSS) from *Escherichia coli* has been studied for its role in stress responses, but true spore formation remains uncommon. Instead, gram-negative bacteria often rely on other survival strategies, such as biofilm formation or the production of protective exopolysaccharides, to endure harsh conditions.

For researchers and practitioners, understanding the absence of spore formation in most gram-negative bacteria is as important as identifying exceptions. This knowledge informs antibiotic treatment strategies, as spores of gram-positive bacteria, like *Clostridium difficile*, require specific conditions to be eradicated. In contrast, gram-negative bacteria are typically more susceptible to certain antibiotics, such as beta-lactams, due to their outer membrane structure. However, the rise of multidrug-resistant strains, like *Pseudomonas aeruginosa* and *Acinetobacter baumannii*, underscores the need for continued research into alternative survival mechanisms.

From a practical standpoint, industries such as food preservation and wastewater treatment must account for the differences in bacterial survival strategies. While gram-positive spores can survive extreme heat and desiccation, gram-negative bacteria are more likely to be controlled through membrane-disrupting agents or environmental modifications. For instance, in food processing, pasteurization effectively targets vegetative cells of gram-negative bacteria, whereas spore-forming gram-positive bacteria may require additional steps like autoclaving.

In conclusion, while spore formation is not a characteristic feature of gram-negative bacteria, exploring this topic reveals the diversity of bacterial survival strategies. Recognizing these differences is essential for developing targeted interventions, whether in clinical settings, industrial processes, or environmental management. By focusing on the unique mechanisms employed by gram-negative bacteria, we can better address the challenges posed by these microorganisms in various contexts.

Is Milky Spore Safe for Vegetable Gardens? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Gram-Negative vs. Gram-Positive Spore Characteristics

Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria differ fundamentally in cell wall structure, but when it comes to spore formation, the distinction becomes even more critical. Gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are well-known spore formers. These spores are highly resistant to extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and desiccation. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria, like *Escherichia coli* and *Salmonella*, do not typically form spores. However, there are rare exceptions, such as *Xanthomonas* and *Achromobacter*, which produce spore-like structures under specific environmental stresses. Understanding these differences is essential for applications in food safety, medicine, and biotechnology.

Analyzing the spore characteristics of Gram-positive bacteria reveals their remarkable resilience. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores can survive in soil for decades, posing a persistent threat to livestock and humans. These spores have a thick, multi-layered structure, including a cortex rich in dipicolinic acid, which stabilizes the DNA and proteins. In contrast, the hypothetical spores of Gram-negative bacteria lack this robust architecture, making them less durable. Practical tip: When sterilizing equipment in a lab or medical setting, autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes is effective against Gram-positive spores but may require longer exposure for Gram-negative spore-like forms, if present.

From an instructive perspective, identifying spores in Gram-positive bacteria involves simple yet effective techniques. A common method is the spore stain, where spores appear green against the red vegetative cells under a microscope. For Gram-negative bacteria, detecting spore-like structures is more challenging and often requires advanced techniques like electron microscopy or molecular assays. Caution: Misidentifying spore-like structures in Gram-negative bacteria can lead to inadequate sterilization protocols, particularly in industries like food processing or pharmaceuticals.

Comparatively, the ability to form spores confers a survival advantage to Gram-positive bacteria in harsh environments. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive boiling water, necessitating pressure cooking at 121°C to ensure food safety. Gram-negative bacteria, despite their lack of true spores, rely on other mechanisms like biofilm formation for survival. Takeaway: In clinical settings, understanding spore characteristics helps in selecting appropriate antibiotics, as spores are inherently resistant to many antimicrobials, whereas vegetative Gram-negative cells may be more susceptible.

Descriptively, the spore formation process in Gram-positive bacteria, known as sporulation, is a complex, multi-stage event triggered by nutrient deprivation. The cell asymmetrically divides, forming a smaller forespore within the larger mother cell. Over time, the forespore develops the protective layers necessary for survival. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria’s spore-like structures are less defined and often a response to extreme stress rather than a programmed developmental process. Practical tip: For researchers studying sporulation, time-lapse microscopy can provide valuable insights into the morphological changes during spore formation, aiding in the development of anti-spore strategies.

Spore Galactic Adventures Mac Compatibility: Does It Work Smoothly?

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers for Gram-Negative Sporulation

Gram-negative bacteria are not typically known for forming spores, a survival mechanism more commonly associated with their gram-positive counterparts. However, recent research has uncovered exceptions, such as *Chromobacterium violaceum* and *Xanthomonas* species, which can produce spore-like structures under specific environmental pressures. Understanding the triggers that induce sporulation in these gram-negative organisms is critical for both ecological and applied sciences, as spores can enhance bacterial survival in harsh conditions and complicate efforts to control pathogens.

Analytical Insight: Environmental stressors act as primary catalysts for sporulation in gram-negative bacteria. Nutrient deprivation, particularly the absence of carbon and nitrogen sources, is a well-documented trigger. For instance, *C. violaceum* initiates spore-like formation when starved of glucose, a process regulated by the sigma factor RpoS. Similarly, desiccation and high salinity levels mimic natural habitat challenges, prompting cells to adopt a dormant, spore-like state. These responses are not universal but depend on the species’ genetic capacity for sporulation, highlighting the need for targeted studies on each organism.

Instructive Guidance: To induce sporulation in gram-negative bacteria for laboratory study, researchers can manipulate growth media and environmental conditions. A common protocol involves culturing cells in minimal media with reduced nutrient concentrations (e.g., 0.1% glucose) for 48–72 hours. Gradual exposure to osmotic stress, achieved by adding 5–10% NaCl, can further enhance spore-like formation. Monitoring cell morphology via phase-contrast microscopy and staining techniques (e.g., spore-specific dyes like malachite green) confirms the success of the process. Caution: Avoid abrupt changes in conditions, as these may trigger cell death rather than sporulation.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike gram-positive sporulation, which is governed by well-characterized pathways (e.g., the *Bacillus subtilis* model), gram-negative sporulation remains poorly understood. Gram-positive spores are encased in a thick protein coat and are highly resistant to heat, radiation, and chemicals. In contrast, gram-negative spore-like structures lack this robust outer layer, exhibiting intermediate resistance. This distinction suggests that gram-negative sporulation may serve a different ecological purpose, such as short-term survival in fluctuating environments rather than long-term persistence.

Descriptive Example: Consider *Xanthomonas campestris*, a plant pathogen that forms spore-like cells in response to oxidative stress induced by host plant defenses. When exposed to reactive oxygen species (ROS) at concentrations mimicking plant immune responses (e.g., 10 mM H₂O₂), *X. campestris* cells undergo morphological changes, including cell wall thickening and DNA condensation. These adaptations enable the bacterium to survive within plant tissues, contributing to its pathogenicity. This example underscores the role of biotic triggers in sporulation, complementing the more commonly studied abiotic factors.

Persuasive Takeaway: While gram-negative sporulation is rare, its implications are profound. For agriculture, understanding how pathogens like *Xanthomonas* form spore-like structures could lead to targeted interventions to disrupt their survival strategies. In biotechnology, harnessing sporulation mechanisms in gram-negative bacteria might offer new avenues for biofilm control or probiotic development. Continued research into environmental triggers is essential to unlock these potential applications and mitigate the risks posed by spore-forming gram-negative pathogens.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores from Your Nightguard

You may want to see also

Survival Advantages of Gram-Negative Spores

Gram-negative bacteria are known for their robust outer membrane, which provides a formidable barrier against many environmental stresses. However, not all gram-negative bacteria form spores, a trait more commonly associated with gram-positive species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. Among gram-negative bacteria, the genus *Bacillus* is an exception, with species like *Bacillus anthracis* forming spores. These spores offer unique survival advantages, particularly in harsh conditions where other bacterial forms might perish. Understanding these advantages sheds light on why spore formation is a critical evolutionary adaptation.

One of the most significant survival advantages of gram-negative spores is their resistance to desiccation. Spores can survive in dry environments for years, even decades, by reducing their metabolic activity to near-zero levels. This dormancy allows them to withstand extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemical disinfectants. For example, spores of *Bacillus anthracis* can remain viable in soil for up to 40 years, posing long-term risks in contaminated areas. This resilience is attributed to the spore’s multilayered structure, including a thick protein coat and a cortex rich in peptidoglycan, which protects the DNA and cellular machinery.

Another critical advantage is the spore’s ability to evade host immune responses. When ingested or inhaled, spores can remain dormant until they reach a more favorable environment, such as the lungs or gastrointestinal tract. Once conditions become suitable, they germinate and resume active growth, often leading to infection. This stealthy mechanism allows gram-negative spores to bypass immediate immune detection, increasing their chances of survival and proliferation. For instance, inhalation of *Bacillus anthracis* spores can lead to inhalational anthrax, a severe and often fatal disease if left untreated.

Practical considerations for managing gram-negative spores include stringent sterilization protocols. Autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes is typically effective, but spores may require longer exposure times. In healthcare settings, surfaces contaminated with spore-forming bacteria should be cleaned with sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine dioxide. For individuals handling spore-forming bacteria in laboratories, personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, masks, and gowns is essential to prevent exposure. Regular monitoring of environments at risk of contamination, such as soil or water sources, can help mitigate the spread of these resilient organisms.

In summary, gram-negative spores possess survival advantages that make them formidable in challenging environments. Their resistance to desiccation, ability to evade immune responses, and tolerance to extreme conditions highlight their evolutionary success. By understanding these traits, we can develop more effective strategies to control and neutralize spore-forming bacteria, ensuring safety in both natural and clinical settings. Whether in research, healthcare, or environmental management, recognizing the unique capabilities of gram-negative spores is crucial for addressing the risks they pose.

Master Spore Asymmetry Mod Installation: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Identification Methods for Gram-Negative Spores

Gram-negative bacteria are primarily known for their outer membrane structure, but the question of whether they form spores complicates their identification. While most gram-negative bacteria are non-spore-forming, exceptions like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* (gram-positive spore-formers) highlight the need for precise methods. Identifying gram-negative spores, though rare, is critical in clinical and environmental settings to differentiate them from contaminants or pathogens. Here, we explore targeted identification methods that combine traditional techniques with advanced technologies.

Microscopy and Staining: The First Line of Detection

Phase-contrast microscopy remains a cornerstone for initial spore detection due to its ability to reveal the refractile nature of spores. However, pairing this with modified Gram staining is essential. Gram-negative spores, if present, will retain the pink or red color of the counterstain, unlike gram-positive spores, which may appear violet. A critical step is heat fixation (80°C for 10 minutes) to ensure spore walls are permeable to stains. For enhanced specificity, add a malachite green stain post-safranin to confirm spore morphology, as this dye penetrates the spore coat more effectively than standard counterstains.

Molecular Techniques: PCR and Beyond

When microscopy falls short, molecular methods like PCR provide definitive answers. Design primers targeting spore-specific genes, such as *spo0A* (a sporulation transcription factor) or *cotE* (spore coat protein), to amplify DNA unique to spore-forming organisms. For gram-negative samples, include a 16S rRNA gene sequencing step to confirm bacterial identity. A practical tip: Use a DNA extraction kit with a mechanical lysis step (e.g., bead-beating) to break spore walls, ensuring adequate DNA yield. This method is particularly useful in environmental samples where spores may be present in low concentrations.

Biochemical and Culture-Based Approaches

Culturing remains invaluable for identifying gram-negative spore-formers. Use selective media like *Bacillus* Cereus Agar (BCA) supplemented with polymyxin B (25 U/mL) to inhibit gram-negative non-spore-formers while allowing spore germination. Incubate at 37°C for 24–48 hours, then observe for characteristic colony morphology. For biochemical confirmation, perform a spore heat resistance test: heat samples at 80°C for 10 minutes, followed by plating on nutrient agar. Growth post-heating indicates spore presence. Caution: False negatives may occur if spores are in the dormant phase, so repeat testing is recommended.

Advanced Imaging: Electron Microscopy and Flow Cytometry

For unambiguous identification, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) offers high-resolution images of spore structures, including the outer membrane and exosporium. Prepare samples using glutaraldehyde fixation and osmium tetroxide staining for contrast. Alternatively, flow cytometry with fluorescent markers like DAPI (for DNA) and SYPRO Ruby (for spore coats) can differentiate spores from vegetative cells. This method is rapid, processing up to 10,000 cells per second, making it ideal for large-scale screening. However, it requires expensive equipment and specialized training, limiting its accessibility.

In conclusion, identifying gram-negative spores demands a multi-faceted approach combining microscopy, molecular techniques, culturing, and advanced imaging. Each method has strengths and limitations, but when used in tandem, they provide a robust framework for accurate detection. Whether in a clinical lab or field study, these tools ensure that even the rarest spore-formers are not overlooked.

Myxococcus Spore Formation Regulation: Mechanisms and Environmental Triggers Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, gram-negative cells are not always spores. Gram-negative bacteria are classified based on their cell wall structure, while spore formation is a separate characteristic related to a bacterium's ability to survive harsh conditions.

Some gram-negative bacteria can form spores, but it is not a common trait. Most spore-forming bacteria are gram-positive, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species.

A gram-negative cell refers to a type of bacterial cell wall structure that does not retain crystal violet dye during Gram staining, while a spore is a dormant, highly resistant cell type formed by certain bacteria to survive extreme environmental conditions.

Yes, there are a few examples of gram-negative spore-forming bacteria, such as *Xenorhabdus* and *Photorhabdus* species, but they are relatively rare compared to gram-positive spore-formers.