The question of whether a spore is a cell is a fascinating one that delves into the intricacies of biology. Spores are highly specialized reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria, designed to survive harsh environmental conditions. While spores share many characteristics with cells, such as being enclosed by a protective membrane and containing genetic material, they are not typically considered fully functional cells in the conventional sense. Instead, spores are often viewed as dormant or resting stages of an organism's life cycle, capable of remaining viable for extended periods until conditions become favorable for growth and development. Understanding the nature of spores and their relationship to cells is crucial for fields like microbiology, botany, and ecology, as it sheds light on the remarkable strategies organisms employ to ensure their survival and propagation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A spore is a reproductive structure, not a cell itself, but it can develop into a new organism under favorable conditions. |

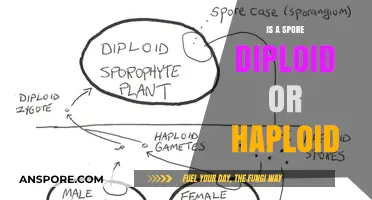

| Type | Spores are typically haploid (single-set of chromosomes) and are produced by bacteria, fungi, algae, and plants. |

| Function | Spores serve as a survival mechanism, allowing organisms to withstand harsh environmental conditions (e.g., heat, cold, drought). |

| Cell vs. Spore | A spore is not a cell but a dormant, resistant structure that can germinate into a new individual, often starting with a single cell. |

| Size | Spores are generally smaller than the cells of the parent organism, ranging from 1 to 50 micrometers in diameter. |

| Wall Composition | Spores have a thick, protective wall composed of sporopollenin (in plants) or other resistant materials, which aids in survival. |

| Metabolism | Spores are metabolically inactive in their dormant state, conserving energy until conditions are suitable for growth. |

| Germination | Under favorable conditions, a spore can germinate, re-entering the active life cycle and developing into a new organism. |

| Examples | Bacterial endospores, fungal spores (e.g., mold, yeast), plant spores (e.g., ferns, mosses), and algal spores. |

| Reproduction | Spores are often produced through asexual or sexual reproduction, depending on the organism. |

| Environmental Resistance | Spores can survive extreme conditions, including radiation, desiccation, and chemicals, due to their robust structure. |

What You'll Learn

- Spore Structure: Spores have protective outer layers, enabling survival in harsh conditions, unlike typical cells

- Cell vs. Spore Function: Cells grow and divide; spores remain dormant until favorable conditions return

- Reproduction Methods: Spores are reproductive units, while cells replicate via mitosis or meiosis

- Survival Mechanisms: Spores resist extreme environments; cells require stable conditions to function

- Biological Classification: Spores are not cells but specialized structures produced by certain organisms

Spore Structure: Spores have protective outer layers, enabling survival in harsh conditions, unlike typical cells

Spores are not your average cells. Unlike typical cells, which are vulnerable to environmental stresses, spores are equipped with specialized protective outer layers that enable them to withstand extreme conditions. These layers, composed of materials like sporopollenin and keratin, act as a shield against desiccation, radiation, and temperature fluctuations. For instance, bacterial endospores can survive for thousands of years in a dormant state, only to revive when conditions become favorable. This remarkable resilience is a direct result of their unique structure, which sets them apart from ordinary cellular life.

Consider the process of spore formation as a strategic retreat. When an organism detects environmental threats, such as nutrient depletion or UV exposure, it initiates sporulation. In fungi, this involves the development of a thick cell wall reinforced with chitin and melanin, while in plants like ferns, spores are encased in a tough outer coat. This protective mechanism is not just about survival—it’s about persistence. For example, fungal spores can remain airborne for extended periods, traveling vast distances before finding a suitable habitat to germinate. This adaptability highlights the evolutionary advantage of spore structure, ensuring species continuity even in the harshest environments.

To understand the practical implications, imagine preserving food or medicine in extreme conditions. Spores’ protective layers inspire technologies like freeze-drying and encapsulation, where sensitive materials are shielded from degradation. In agriculture, spore-based biopesticides offer a sustainable alternative to chemical treatments, as their resilience ensures long-term efficacy. Even in space exploration, spores are studied for their potential to survive extraterrestrial conditions, serving as models for astrobiology research. By mimicking spore structure, scientists aim to develop materials and systems that thrive under stress, bridging biology and engineering.

However, the very features that make spores resilient also pose challenges. Their durability can lead to contamination in sterile environments, such as hospitals or food processing facilities. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive boiling temperatures, requiring specialized sterilization techniques like autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes. Similarly, fungal spores in indoor environments can trigger allergies and respiratory issues, necessitating air filtration systems with HEPA filters. Understanding spore structure is thus critical not only for harnessing their benefits but also for mitigating their risks.

In essence, the protective outer layers of spores are a testament to nature’s ingenuity. They defy the fragility of typical cells, offering lessons in survival and adaptability. Whether in scientific research, industrial applications, or everyday life, the study of spore structure provides actionable insights. From preserving life in extreme conditions to combating contamination, spores remind us that resilience is not just about enduring—it’s about thriving against all odds.

Circle of Spores Druids: Poison Immunity Explained in D&D 5e

You may want to see also

Cell vs. Spore Function: Cells grow and divide; spores remain dormant until favorable conditions return

Cells are the fundamental units of life, perpetually engaged in growth, division, and metabolic activity. They require a stable environment with access to nutrients, water, and energy to thrive. In contrast, spores are survival specialists, designed to endure harsh conditions that would be lethal to active cells. While both are products of cellular processes, their functions diverge sharply. Cells prioritize proliferation and maintenance, whereas spores focus on preservation and resilience. This distinction highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of organisms that produce spores, ensuring continuity even in adversity.

Consider the lifecycle of a bacterium like *Bacillus subtilis*. Under favorable conditions, it grows and divides rapidly through binary fission, a process that doubles its population in as little as 20 minutes. However, when nutrients deplete or environmental stressors arise, it forms an endospore—a dormant, highly resistant structure. This spore can withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation, remaining viable for centuries. Unlike the active cell, the spore does not metabolize or replicate; it simply waits. This strategic dormancy is a testament to the spore’s role as a cellular time capsule, preserving genetic material until conditions improve.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this cell-spore dichotomy is crucial in fields like medicine and food preservation. For instance, bacterial spores in food can survive standard cooking temperatures (e.g., 100°C), necessitating methods like pressure cooking (121°C) to ensure safety. In healthcare, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* pose challenges due to their resistance to antibiotics and disinfectants. Conversely, harnessing spore dormancy mechanisms could inspire innovations in biotechnology, such as preserving vaccines or enzymes without refrigeration. The key takeaway: cells are the engines of life, while spores are its safeguards.

To illustrate further, compare plant cells and fungal spores. Plant cells actively photosynthesize, grow, and differentiate into tissues, driving the organism’s development. Fungal spores, however, are dispersed agents of survival and colonization. A single mushroom can release trillions of spores, each capable of lying dormant until landing in a suitable substrate. This disparity in function underscores the spore’s role as a minimalist, durable vessel, stripped of unnecessary cellular machinery. While cells are the architects of life’s complexity, spores are its endurance champions.

In essence, the cell-spore relationship exemplifies nature’s duality: creation versus preservation. Cells embody dynamism, driving growth and adaptation, while spores represent stasis, ensuring survival against all odds. This functional divergence is not a competition but a collaboration, a balance between thriving in the present and preparing for the future. Whether in a laboratory, kitchen, or forest floor, recognizing this distinction empowers us to manipulate, mitigate, or mimic these processes for practical benefit. Cells and spores, though linked by biology, serve as reminders of life’s resilience and ingenuity.

Can Spores Grow in Stool? Understanding Microbial Growth in Feces

You may want to see also

Reproduction Methods: Spores are reproductive units, while cells replicate via mitosis or meiosis

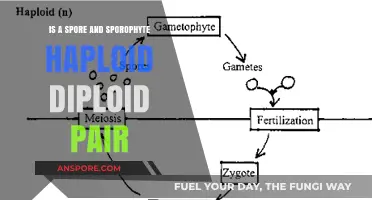

Spores and cells, though both fundamental to life, diverge sharply in their reproductive strategies. Cells, the basic units of life, primarily replicate through mitosis or meiosis—processes that ensure genetic continuity and diversity. Mitosis produces two genetically identical daughter cells, essential for growth and repair, while meiosis generates four genetically unique cells, crucial for sexual reproduction. These mechanisms are finely tuned, occurring within the protective environment of an organism, and rely on the cell’s internal machinery to divide accurately. Spores, however, are not cells in the conventional sense; they are specialized reproductive units produced by certain organisms, such as fungi, plants, and some bacteria. Unlike cells, spores are dormant, resilient structures designed for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions, not immediate replication.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a prime example of spore-based reproduction. Ferns produce spores in structures called sporangia, which are released into the environment. These spores are not miniature ferns but single-celled entities that, under favorable conditions, germinate into a gametophyte—a small, heart-shaped structure. The gametophyte then produces sperm and eggs, which unite to form a new fern plant. This process contrasts sharply with cellular replication, where division occurs within the organism itself, ensuring immediate continuity. Spores, by design, are external agents of propagation, optimized for dispersal and endurance rather than rapid multiplication.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these reproductive methods has tangible applications. For instance, in agriculture, spore-producing fungi like *Trichoderma* are used as biocontrol agents to combat plant pathogens. Their ability to form spores allows them to persist in soil, ready to activate when conditions are right. Conversely, controlling cellular replication is key in medical treatments like chemotherapy, which targets rapidly dividing cancer cells. While spores are engineered for survival and dispersal, cells are optimized for growth and repair within a living organism. This distinction underscores the importance of tailoring strategies to the unique mechanisms of each.

A comparative analysis reveals the trade-offs between these methods. Spores sacrifice immediate replication for long-term survival and dispersal, making them ideal for organisms in unpredictable environments. Cells, on the other hand, prioritize rapid and controlled division, essential for multicellular organisms’ maintenance and adaptation. For example, bacterial spores can survive extreme temperatures, radiation, and desiccation, whereas human cells require a stable internal environment to divide successfully. This contrast highlights the evolutionary elegance of both strategies, each adapted to its ecological niche.

In conclusion, while spores and cells both serve reproductive functions, their methods reflect distinct evolutionary priorities. Spores are not cells but specialized units designed for survival and dispersal, whereas cells replicate through precise internal mechanisms like mitosis and meiosis. Recognizing these differences is crucial for fields ranging from biology to biotechnology, offering insights into how life perpetuates itself in diverse forms and environments. Whether harnessing spores for agricultural resilience or targeting cellular division in medicine, understanding these methods empowers practical innovation.

Gills, Pores, and Teeth: Unlocking the Secrets of Spore Production

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Spores resist extreme environments; cells require stable conditions to function

Spores are nature's ultimate survivalists, capable of enduring conditions that would destroy most life forms. Unlike typical cells, which require a narrow range of temperature, pH, and nutrient availability to function, spores can withstand extremes such as boiling heat, freezing cold, and even the vacuum of space. This resilience is achieved through a combination of desiccation, thick protective coatings, and metabolic shutdown, allowing spores to remain dormant for centuries until conditions improve. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can survive temperatures up to 120°C, while human cells begin to denature at just 42°C. This stark contrast highlights the spore’s unparalleled ability to resist environmental stress.

To understand the spore’s survival advantage, consider its structure compared to a typical cell. A spore’s outer layer, composed of proteins like sporopollenin and dipicolinic acid, acts as a barrier against radiation, chemicals, and physical damage. In contrast, a cell’s membrane is fragile, relying on a stable environment to maintain its integrity. For practical application, this means spores can be used in biotechnology for long-term storage of microorganisms, while cells require controlled conditions like incubators at 37°C and 5% CO₂ to remain viable. This difference is why spores are found in extreme habitats, from hot springs to the Arctic, while most cells are confined to temperate, resource-rich environments.

The spore’s ability to enter dormancy is a key survival mechanism. During sporulation, the organism reduces its metabolic activity to near zero, halting processes like DNA replication and protein synthesis. This state minimizes energy consumption and damage from reactive oxygen species, which are common in harsh environments. Cells, however, must maintain active metabolism to repair damage and sustain life, making them vulnerable to environmental fluctuations. For example, a spore can survive in nutrient-depleted soil for decades, while a cell without glucose or oxygen would perish within minutes. This metabolic flexibility underscores the spore’s role as a master of endurance.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore survival mechanisms has significant implications for industries like food safety and space exploration. Spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, for instance, can survive pasteurization temperatures (72°C for 15 seconds) and cause foodborne illness if conditions later become favorable for growth. To combat this, food manufacturers use high-pressure processing (HPP) or irradiation to destroy spores. Similarly, NASA studies spores to understand how life might survive interplanetary travel, as evidenced by experiments on the International Space Station showing *Bacillus* spores can endure years of exposure to space conditions. These applications demonstrate how the spore’s resilience challenges and informs human innovation.

In conclusion, the spore’s survival mechanisms—its robust structure, metabolic dormancy, and resistance to extremes—set it apart from cells, which demand stability to thrive. This distinction is not just biological trivia but a practical guide for fields ranging from microbiology to astrobiology. By studying spores, we gain insights into life’s limits and possibilities, whether in preserving food, combating pathogens, or searching for life beyond Earth. The spore’s ability to endure where cells cannot is a testament to nature’s ingenuity in overcoming adversity.

Conifer Reproduction: Do They Use Spores or Seeds to Multiply?

You may want to see also

Biological Classification: Spores are not cells but specialized structures produced by certain organisms

Spores are often mistaken for cells due to their microscopic size and role in reproduction, but they are fundamentally different. Unlike cells, which are the basic structural and functional units of life, spores are specialized structures produced by certain organisms for survival and dispersal. This distinction is crucial in biological classification, as it highlights the unique functions and characteristics of spores. For instance, while cells carry out metabolic processes and maintain life, spores are dormant, resilient forms designed to withstand harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or lack of nutrients.

To understand this classification, consider the life cycles of spore-producing organisms like fungi, plants (e.g., ferns and mosses), and some bacteria. In these organisms, spores are not part of the normal cellular activity but are produced under specific environmental cues. For example, fungal spores are released into the air to travel long distances, while plant spores germinate into new individuals under favorable conditions. This specialized role sets spores apart from cells, which are continuously active in growth, repair, and reproduction. A key takeaway is that spores are not cells but rather survival mechanisms, a distinction that underscores their importance in the biological world.

From a practical standpoint, recognizing that spores are not cells has implications for fields like medicine, agriculture, and environmental science. For instance, fungal spores can cause allergies in humans, and understanding their structure helps in developing targeted treatments. In agriculture, spore-based biofungicides are used to control plant diseases without harming beneficial organisms. To effectively utilize spores, it’s essential to know their characteristics: they are lightweight, easily dispersed, and can remain viable for years. For example, a single mold colony can release millions of spores, making them a significant factor in indoor air quality.

Comparatively, while cells are universal across life forms, spores are exclusive to specific groups of organisms. This exclusivity reflects their evolutionary adaptation to particular challenges. For example, bacterial endospores can survive boiling temperatures, a trait no ordinary cell possesses. Similarly, fern spores can lie dormant in soil for decades before germinating. This comparative analysis highlights the specialized nature of spores, reinforcing their classification as distinct from cells. By focusing on these differences, scientists can better harness the potential of spores in biotechnology and conservation efforts.

In conclusion, spores are not cells but specialized structures with unique roles in survival and dispersal. Their classification as non-cellular entities is based on their dormant, resilient nature and specific functions in the life cycles of certain organisms. Understanding this distinction is vital for practical applications, from medical treatments to agricultural innovations. By appreciating the unique characteristics of spores, we can leverage their potential while avoiding misconceptions that arise from conflating them with cells. This clarity in biological classification paves the way for advancements in science and technology.

Unlock Free Spore DLC: Easy Tips and Tricks Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, a spore is a type of cell produced by certain organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and plants, as a means of reproduction or survival.

The primary function of a spore is to ensure the survival of the organism in harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, lack of nutrients, or desiccation, and to facilitate dispersal and reproduction.

Spores differ among organisms. For example, bacterial spores (endospores) are highly resistant structures, fungal spores are involved in reproduction and dispersal, and plant spores (like those in ferns) are part of their life cycle.

Yes, under favorable conditions, spores can germinate and grow into new organisms. For instance, fungal spores develop into hyphae, and plant spores grow into gametophytes.