Streptococcus pyogenes, a Gram-positive bacterium commonly known as group A Streptococcus (GAS), is a significant human pathogen responsible for a wide range of infections, from mild conditions like pharyngitis and impetigo to severe invasive diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Despite its clinical importance, S. pyogenes is not spore-forming. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which produce highly resistant endospores to survive harsh environmental conditions, S. pyogenes relies on its ability to colonize and evade the host immune system for survival. This distinction is crucial, as spore formation is a characteristic feature of certain bacterial genera, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, but is entirely absent in Streptococcus pyogenes, making it more susceptible to environmental stressors and standard disinfection methods.

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Definition: Understanding what spore formation means in bacterial species like Streptococcus pyogenes

- S. Pyogenes Characteristics: Examining if Streptococcus pyogenes has spore-forming capabilities based on its biology

- Survival Mechanisms: Exploring alternative survival strategies of S. pyogenes without spore formation

- Comparative Analysis: Comparing S. pyogenes to spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium species

- Clinical Implications: Discussing the impact of non-spore-forming nature on S. pyogenes infections and treatment

Spore Formation Definition: Understanding what spore formation means in bacterial species like Streptococcus pyogenes

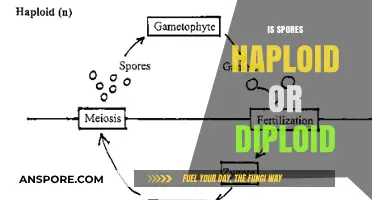

Spore formation is a survival mechanism employed by certain bacteria to endure harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or exposure to antimicrobials. This process involves the differentiation of a bacterial cell into a highly resistant, dormant structure known as a spore. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can remain viable for extended periods, often years, until conditions become favorable for growth again. Understanding spore formation is crucial because it highlights the resilience of certain bacterial species and their ability to persist in diverse environments. However, not all bacteria possess this capability, and Streptococcus pyogenes is a notable example of a non-spore-forming pathogen.

To determine whether Streptococcus pyogenes is spore-forming, it’s essential to examine its biological characteristics. S. pyogenes, a Gram-positive coccus, is primarily known for causing infections like strep throat and impetigo. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus anthracis or Clostridium botulinum, S. pyogenes lacks the genetic machinery required for sporulation. Its survival strategies instead rely on rapid replication, evasion of the host immune system, and production of virulence factors like M proteins and streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins. This distinction is critical for clinicians and researchers, as spore-forming bacteria often require specialized treatment approaches, such as spore-specific antibiotics or sterilization techniques, which are unnecessary for S. pyogenes.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in S. pyogenes simplifies infection control measures. Spore-forming bacteria demand rigorous decontamination protocols, including autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes or the use of sporicidal disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid. In contrast, S. pyogenes is effectively eliminated by standard disinfection methods, such as 70% ethanol or quaternary ammonium compounds. For healthcare settings, this means routine cleaning practices are sufficient to prevent transmission, reducing the need for more resource-intensive sterilization procedures. However, it’s important to note that S. pyogenes can still survive on surfaces for days, emphasizing the need for consistent hygiene practices.

Comparatively, the inability of S. pyogenes to form spores also influences its susceptibility to antibiotics. Spore-forming bacteria often exhibit resistance to many antimicrobials due to the impermeability of their spore coats. S. pyogenes, however, remains treatable with common antibiotics like penicillin or amoxicillin, typically administered at dosages of 250–500 mg every 6–8 hours for adults, depending on the infection severity. This susceptibility underscores the importance of accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment to prevent complications like rheumatic fever or invasive group A streptococcal disease. Understanding these differences ensures appropriate clinical management and highlights the unique challenges posed by spore-forming versus non-spore-forming pathogens.

In conclusion, while spore formation is a remarkable adaptation in certain bacteria, Streptococcus pyogenes does not possess this capability. This characteristic simplifies infection control and treatment strategies, making it a more manageable pathogen in clinical settings. However, its ability to cause significant disease underscores the need for vigilance and adherence to standard hygiene and antimicrobial protocols. By distinguishing between spore-forming and non-spore-forming bacteria, healthcare professionals can tailor their approaches to effectively combat infections and prevent outbreaks.

Exploring Fungi Reproduction: Sexual, Asexual, or Both?

You may want to see also

S. Pyogenes Characteristics: Examining if Streptococcus pyogenes has spore-forming capabilities based on its biology

Streptococcus pyogenes, a Gram-positive bacterium responsible for a range of human infections from strep throat to invasive diseases like necrotizing fasciitis, lacks the ability to form spores. This characteristic is critical for understanding its survival strategies and susceptibility to environmental stressors. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus anthracis, which can endure harsh conditions like desiccation or extreme temperatures by forming dormant spores, S. pyogenes relies on its vegetative form for survival. This limitation makes it more vulnerable to disinfection methods, including heat, alcohol, and common antiseptics, which are routinely used in clinical and household settings to control its spread.

Analyzing the biology of S. pyogenes reveals why spore formation is absent in this species. As a facultative anaerobe, it thrives in environments rich in oxygen but can also survive in its absence, primarily colonizing the human respiratory tract and skin. Its survival mechanisms focus on rapid replication, evasion of the host immune system, and production of virulence factors like M proteins and streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins. These adaptations allow it to cause disease efficiently but do not include the complex genetic and metabolic pathways required for sporulation, which are typically found in phylogenetically distinct bacteria like those in the Firmicutes phylum.

From a practical standpoint, the non-spore-forming nature of S. pyogenes has significant implications for infection control. Healthcare providers can effectively decontaminate surfaces and medical equipment using standard disinfection protocols, such as 70% ethanol or quaternary ammonium compounds, which target vegetative cells. However, this also underscores the importance of prompt treatment in infected individuals, as the bacterium’s reliance on active metabolism makes it susceptible to antibiotics like penicillin, which inhibit cell wall synthesis. For example, a typical adult dose of penicillin V for treating streptococcal pharyngitis is 250–500 mg every 12 hours for 10 days, ensuring eradication of the pathogen before it can spread or cause complications.

Comparatively, the absence of spore formation in S. pyogenes contrasts sharply with pathogens like Clostridioides difficile, which can persist in healthcare environments as spores, leading to recurrent infections. This distinction highlights the importance of tailoring infection control measures to the specific biology of the pathogen. While S. pyogenes requires immediate attention due to its rapid proliferation and potential for severe disease, its inability to form spores simplifies its management in clinical settings. Public health efforts should focus on early diagnosis, appropriate antibiotic use, and hygiene practices to limit transmission, rather than on the more complex strategies needed for spore-forming organisms.

In conclusion, the non-spore-forming nature of Streptococcus pyogenes is a defining feature that shapes its ecology, pathogenesis, and control. By understanding this biological limitation, healthcare professionals and researchers can more effectively combat infections caused by this bacterium. Practical steps, such as adhering to antibiotic regimens and maintaining rigorous hygiene, remain cornerstone strategies for managing S. pyogenes, ensuring that its impact on human health is minimized despite its lack of spore-based resilience.

Can Mold Spores Die? Uncovering the Truth About Their Survival

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Exploring alternative survival strategies of S. pyogenes without spore formation

Streptococcus pyogenes, the bacterium responsible for strep throat and invasive infections like necrotizing fasciitis, lacks the ability to form spores—a survival mechanism employed by other pathogens like Clostridium difficile. This absence raises the question: How does S. pyogenes persist in hostile environments without this evolutionary advantage? The answer lies in its arsenal of alternative strategies, each finely tuned to exploit niches within and outside the human host.

Biofilm Formation: A Shield Against Adversity

One of S. pyogenes’s most effective survival tactics is biofilm formation. These structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix provide protection against antibiotics, host immune responses, and environmental stressors. For instance, in chronic wound infections, S. pyogenes biofilms can reduce antibiotic efficacy by up to 1,000-fold compared to planktonic cells. To combat this, clinicians often recommend biofilm-disrupting agents like DNase or N-acetylcysteine alongside standard antibiotics. Patients with recurrent infections should be monitored for biofilm presence, as early detection can prevent treatment failure.

Phenotypic Switching: A Cloak of Invisibility

S. pyogenes employs phenotypic switching, altering surface proteins like M proteins to evade immune detection. This mechanism allows it to persist in the host without triggering a full immune response. For example, studies show that M protein variation can reduce phagocytosis by up to 70%. Vaccination efforts targeting conserved M protein epitopes are under development, but until then, healthcare providers should emphasize complete antibiotic courses to prevent relapse due to immune evasion.

Persistence in Asymptomatic Carriers: Silent Reservoirs

Up to 20% of school-aged children are asymptomatic carriers of S. pyogenes, harboring the bacterium in their throats without symptoms. This carrier state serves as a community reservoir, facilitating transmission during outbreaks. Public health strategies should focus on identifying carriers through rapid antigen testing, particularly in high-risk settings like schools and nursing homes. Prophylactic antibiotics are generally not recommended for carriers unless they are in close contact with immunocompromised individuals.

Environmental Resilience: Surviving Outside the Host

S. pyogenes can survive on surfaces for up to 6 days, depending on humidity and temperature. This resilience enables indirect transmission via fomites, a critical factor in healthcare-associated infections. To mitigate this, disinfection protocols should include EPA-approved agents effective against Gram-positive bacteria, with contact times of at least 10 minutes. Hand hygiene remains paramount, with alcohol-based rubs (minimum 60% ethanol) reducing transmission by 95% in clinical settings.

Genetic Flexibility: Adapting to Stress

S. pyogenes’s small genome encodes a surprisingly robust stress response system. For example, the bacterium upregulates chaperone proteins like GroEL during heat stress, ensuring protein stability. This adaptability allows it to survive in diverse environments, from the human throat to contaminated surfaces. Researchers are exploring inhibitors of these stress response pathways as potential adjunctive therapies, though clinical applications remain experimental.

In summary, S. pyogenes compensates for its inability to form spores through a multifaceted survival toolkit. Understanding these mechanisms not only highlights the bacterium’s ingenuity but also informs targeted interventions to disrupt its persistence and transmission. From biofilm disruption to carrier screening, each strategy addresses a specific vulnerability, offering a roadmap for more effective control of this pervasive pathogen.

Do Land Plants Produce Spores Through Meiosis? Unraveling the Process

You may want to see also

Comparative Analysis: Comparing S. pyogenes to spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium species

Streptococcus pyogenes, a common human pathogen responsible for infections ranging from pharyngitis to necrotizing fasciitis, lacks the ability to form spores. This contrasts sharply with spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium species, which produce highly resistant endospores as a survival mechanism. Understanding this distinction is crucial for clinical management, as it influences treatment strategies, disinfection protocols, and patient outcomes.

From an analytical perspective, the absence of spore formation in S. pyogenes simplifies its eradication in clinical settings. Unlike Clostridium species, which can survive extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and antibiotics due to their spore state, S. pyogenes is more susceptible to standard disinfection methods. For instance, alcohol-based hand sanitizers (at least 60% ethanol or 70% isopropanol) effectively kill S. pyogenes within seconds, whereas Clostridium spores require autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes or specialized sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide vapor. This difference underscores the importance of tailoring infection control measures to the specific pathogen.

Instructively, healthcare providers must recognize that S. pyogenes infections, such as cellulitis or impetigo, respond well to beta-lactam antibiotics (e.g., penicillin 250–500 mg orally every 6 hours for adults) or macrolides in penicillin-allergic patients. In contrast, Clostridium infections, like tetanus or botulism, often require antitoxins (e.g., tetanus immunoglobulin 250–500 units intramuscularly) in addition to antibiotics such as metronidazole (500 mg orally every 6 hours). Misidentifying S. pyogenes as spore-forming could lead to unnecessary use of sporicidal treatments, delaying appropriate therapy.

Persuasively, the non-spore-forming nature of S. pyogenes highlights its reliance on active replication and host interaction for survival. This makes it a prime target for phage therapy or antimicrobial peptides, emerging strategies that exploit bacterial vulnerabilities. Conversely, the spore-forming ability of Clostridium species necessitates research into spore germination inhibitors, a more complex and resource-intensive approach. Clinicians and researchers should prioritize interventions based on these fundamental biological differences.

Descriptively, the life cycles of S. pyogenes and Clostridium species illustrate their contrasting survival strategies. S. pyogenes thrives in warm, moist environments like the human throat or skin, relying on rapid division and toxin production to cause disease. Clostridium species, however, can persist in soil or contaminated wounds as dormant spores for years, germinating only when conditions become favorable. This resilience explains why Clostridium difficile infections often recur after antibiotic treatment disrupts gut flora, while S. pyogenes infections typically resolve with appropriate therapy.

In conclusion, comparing S. pyogenes to spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium species reveals critical differences in survival mechanisms, treatment approaches, and infection control. Recognizing these distinctions enables more effective clinical management, from antibiotic selection to disinfection protocols, ultimately improving patient care and public health outcomes.

Mastering Smeargle's Spore Move in Pokémon Emerald: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Clinical Implications: Discussing the impact of non-spore-forming nature on S. pyogenes infections and treatment

Streptococcus pyogenes, the bacterium responsible for conditions like strep throat and cellulitis, does not form spores. This characteristic significantly influences its clinical behavior and treatment strategies. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which can survive harsh conditions by entering a dormant state, S. pyogenes relies on active replication and immediate access to nutrients. This non-spore-forming nature makes it more susceptible to environmental stressors, such as desiccation and disinfectants, limiting its survival outside the host. However, it also means that infections are typically acute and localized, requiring prompt intervention to prevent complications like rheumatic fever or invasive disease.

From a treatment perspective, the non-spore-forming nature of S. pyogenes simplifies eradication efforts. Antibiotics like penicillin (250–500 mg every 6 hours for adults) or amoxicillin (500 mg every 8 hours) effectively target actively dividing cells, as the bacterium lacks the protective spore structure. This contrasts with spore-forming pathogens, which often require spore-specific agents or prolonged therapy. For instance, a 10-day course of penicillin is usually sufficient to eliminate S. pyogenes, whereas Clostridium difficile, a spore-former, may necessitate multiple rounds of treatment with vancomycin or fidaxomicin. Adherence to the full antibiotic course is critical, as premature discontinuation can lead to relapse or antibiotic resistance.

The non-spore-forming nature of S. pyogenes also impacts infection control practices. Since the bacterium does not persist in the environment as spores, standard disinfection protocols, such as alcohol-based hand sanitizers or bleach solutions, are highly effective in healthcare settings. However, this does not diminish the importance of prompt diagnosis and isolation of infected patients, particularly in crowded environments like schools or nursing homes. For example, children with strep throat should remain home for at least 24 hours after starting antibiotics to minimize transmission, as the bacterium spreads primarily through respiratory droplets and direct contact.

Despite its susceptibility to antibiotics, the non-spore-forming nature of S. pyogenes highlights the need for vigilance in managing complications. Invasive infections, such as necrotizing fasciitis, require aggressive treatment, including surgical debridement and high-dose intravenous antibiotics (e.g., penicillin G 2–4 million units every 4 hours). The bacterium’s reliance on active replication means that delaying treatment can allow rapid tissue destruction, emphasizing the importance of early recognition and intervention. Additionally, the absence of spores does not preclude the development of antibiotic resistance, as seen in some strains with reduced susceptibility to macrolides.

In summary, the non-spore-forming nature of S. pyogenes shapes its clinical management by enabling effective treatment with standard antibiotics, simplifying infection control, and necessitating prompt intervention to prevent severe outcomes. While this characteristic reduces environmental persistence, it underscores the importance of timely diagnosis and adherence to treatment protocols. Clinicians must remain aware of the bacterium’s unique vulnerabilities and potential complications to optimize patient care and prevent transmission.

Crafting Dragon Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide to Magical Creation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Streptococcus pyogenes is not a spore-forming bacterium. It is a Gram-positive, non-spore-forming coccus.

Non-spore-forming bacteria, such as Streptococcus pyogenes, do not produce endospores, which are highly resistant structures that allow some bacteria to survive harsh conditions.

Streptococcus pyogenes is relatively fragile and does not survive well outside the host environment for extended periods, as it lacks the protective spore mechanism.

While spore-forming bacteria can survive harsh conditions, non-spore-forming bacteria like Streptococcus pyogenes are generally more susceptible to disinfection and environmental stresses, making them easier to control in clinical settings.

No, none of the streptococcal species, including Streptococcus pyogenes, are known to form spores. They are all non-spore-forming bacteria.